With public health in the balance, Dr. Tomchik declared war on the patient

After a year of persistent headlines, the Elkhart County health officer remained defiant.

An angry public crowded into meeting rooms and demanded a resignation.

The board appointed to oversee local health issues was divided and ineffective.

Elected officials vehemently objected to the state’s attempt to override local control.

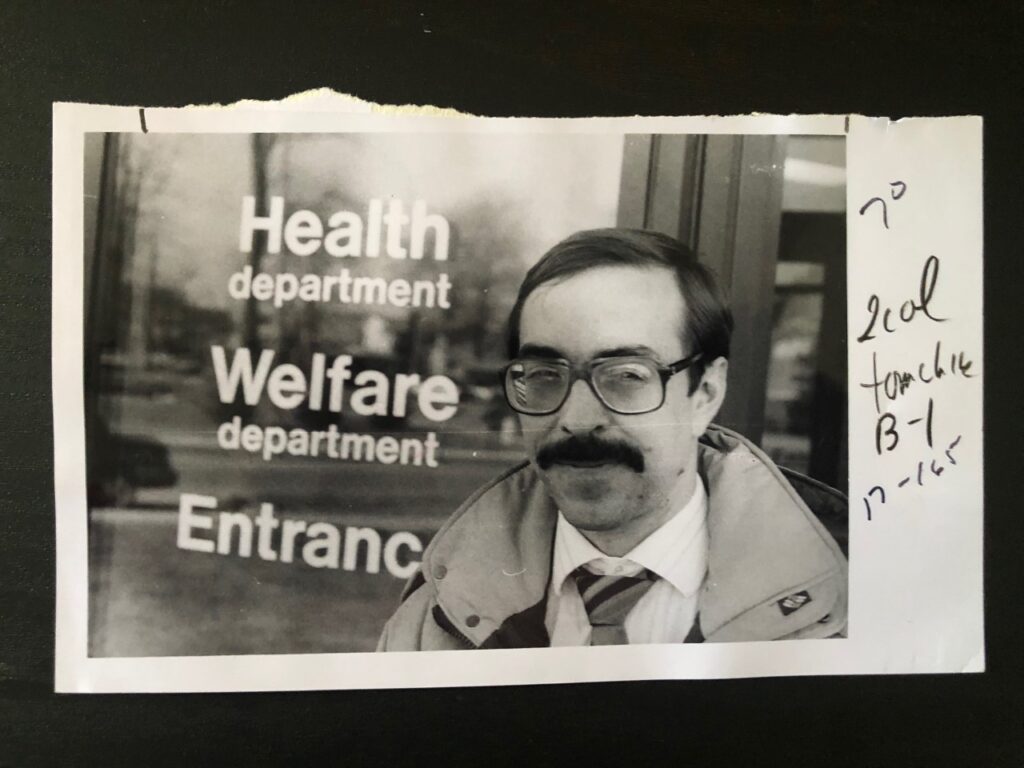

In the opening days of the AIDS epidemic, and in a place with growing environmental concerns, Elkhart County was mired in turmoil over the functions of its public health department. And whether the war was years in the making or just started upon the arrival of Dr. Robert Tomchik in the summer of 1988, the battle was joined and the casualties would be many.

A healthy cost

With nearly 100 employees under Dr. Stanley Reedy’s guidance, Elkhart County earned the state’s Excellence in Public Health Award in 1987. But the department also was getting unwanted notice from elected officials, who were increasingly concerned with the local cost of public health.

The county hired Reedy as its first full-time doctor in 1975. After three years of his leadership, the health department budget was set at $548,000. Less than a decade after that, the annual funding request was $2.1 million.

Reedy was gone, having resigned in March 1987 to take an assignment with the Mennonite Central Committee in Thailand. As the search for a replacement slogged through a year and more, the county commissioners and council were increasingly anxious to assert their influence.

Dr. Robert S. Tomchik came here ready to listen to them. With Midwest collegiate training and a Goshen native as his wife, he said upon his introduction, “I consider this home.”

The homecoming lasted all of 461 days.

The boiling point

The short path to lengthy complaints began almost immediately after Tomchik arrived from Florida.

From the Elkhart Truth Collection files, reporter Krista Kennedy wrote at the start of the summer 1988 about the many obstacles the doctor had in front of him when starting the job, including a communication gap with elected officials. “Tomchik sees the current problems as solvable,” she wrote. “He referred to the problems as ‘unusual’ given the commitment shown ‘to all facets of health care’ by those at various levels of government.”

That commitment clearly was neither unconditional nor current.

Three county councilmen, backed by Farm Bureau in the summer of 1987, approached Elkhart General Hospital about taking over the department’s home health services. Both the council and commissioners were moving forward in the summer of 1988 with a proposed $40,000 study with an expectation of creating change in everyday department operations.

Just a week on the job in Elkhart County, Tomchik spent hours behind closed doors meeting with the three commissioners. “We were pleased and quite impressed with him,” commissioner Marvin Riegsecker reported after one executive session.

But what was the relationship that was being built?

On Feb. 7, 1989, as part of a week-long series on the health department’s past and present, Truth reporter Tom Price wrote, “Once upon a time in Elkhart County, the commissioners, the council and advocates for the health department were of one mind. Although that may sound like a fairy tale to those embroiled in today’s ongoing conflict …”

George White, who served as council president during Reedy’s time in Elkhart County, attributed the change in attitude to council members who joined in the mid-1980s. They began to “interfere” with operations, he said. “The council appropriated funds, set a budget, and stayed out,” White told The Truth for that article. “That reduces the area of conflict.”

But the health department and elected officials had had public squabbles before. Some went back a decade or more, as both sides jockeyed for position on spending, services, and even day-to-day decisions.

In a particularly biting story from 1979, then-commissioner Tom Romberger took issue with Dr. Reedy’s decision to call a snow day when the rest of the government offices were open. “When somebody strays off the track, sometimes you have to wrap their knuckles to get ‘em back on it,” Romberger said at the time.

From the personal came the political. Running for re-election in 1988, council president Jack Donis strongly asserted the elected officials’ hands-on approach.

“Streamline and strengthen the internal management of the various departments through improved personnel guidelines, additional training, and the use of good management practices,” Donis wrote in a candidate questionnaire sent by Truth reporters. “… (T)he council needs to carefully scrutinize any request and insist that the departments handle their finances in a professional and businesslike manner so that taxpayers get the best possible government service at the lowest possible tax rate.”

Specific to the health department concerns up to and including the Tomchik era, former councilman Gary O’Dell said in February 1989, “I think that the issue is not what they’re arguing about today. It comes from a buildup of many years – over little contentions, ill feelings over a lot of little things. I think the issue of today is kind of an end result.”

‘Religious intensity’

“Tomchik’s arrival has sparked a new round in the boxing match,” Krista Kennedy wrote a couple days later in February 1989. “Those who stand at the sidelines worry about whether their home health care nurse will pay a visit to them or if their grandchildren will be granted the pure waters to drink from as they did.

“Meanwhile, departmental employees and administrators, members of the board of health and county commissioners and council negotiate, aiming for a common ground from which to build a relationship of trust and peace.”

Conflict paralyzed the public health office. In anticipation of the IUSB findings, the council attempted to slash the department’s 1989 spending plan by 75 percent. Employees staged walkouts in protest of interference by both the council and Tomchik. Three division heads resigned because they said Tomchik was keeping files on those he sought to fire.

Tomchik described the infighting as having a quality of “religious intensity. … Some of the names I’ve been called, (like) Judas, reveal that religious fervor. … It’s been a real shock coming to a community that prides itself on its Christian influence. I’ve never encountered anything that quite resembles this – ever.”

The Feb. 10, 1989, article continued, “‘I came in and I said we’re going to cooperate with them,’ said Tomchik, who received much criticism for becoming ‘too chummy’ with members of the council and commissioners. ‘So what I brought was a drastic radical change in approach.’”

When the preliminary IUSB report was shared, the researcher recommended the county withdraw from home health and mother-child services. “The health department has not decided if its primary mission is prevention or cure; whether its target population is the community or individuals …” William Hojnacki wrote, adding the services targeted were not required by law to be offered.

On the other side, the IUSB proposal encouraged a task-force approach to sexually transmitted diseases, greater focus on preventing suicides and teen auto accidents, and a strategy to review program results and spending.

Upon hearing the initial outcomes, the appointed health board urged county leaders to “continue (health department) service unmolested in its present approach.”

The fight for control

By the summer of 1989, Tomchik stood against a petition with hundreds of signatures calling for his firing. At least one health board member was active in challenging his fellow members to take action. But the doctor announced he had emerged victorious in the “win-or-lose situation” with his own employees.

“Essentially, what we’ve had going on is a clear and simple power struggle as to who was going to run the department. When you have a power struggle that strong and played out in public – it wasn’t clear who was going to win. … Those who tried to take control of the department failed. So they are leaving the department.”

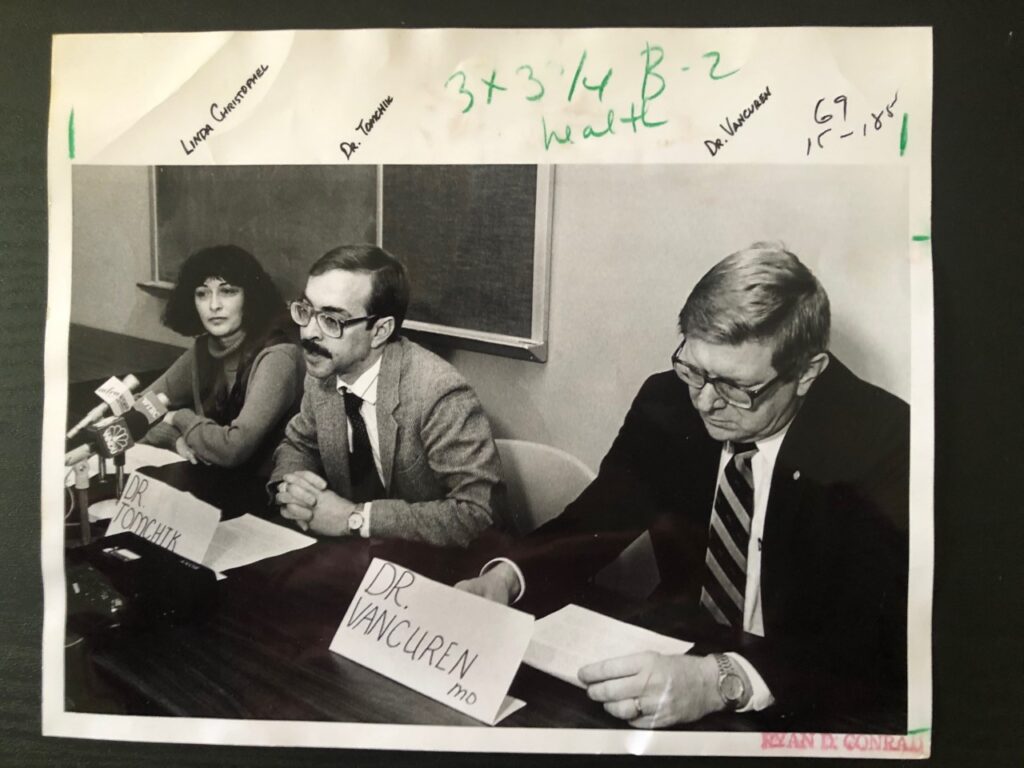

State officials were beginning to weigh in on Elkhart County’s situation.

In preparation for Tomchik’s first performance evaluation, the health board retained attorney Jim Brotherson. The lawyer’s 162-page report “appeared to lean toward the discharge of Tomchik,” according to Dr. Robert Moon, vice president of the Indiana State Board of Health.

Instead, the county board wavered. The doctor stayed on.

As staff complaints about stressful work conditions, ineffective management, and job insecurity increased, local health board member Terry Kaeser publicly called for the doctor’s firing. “I would hope the board has the guts enough to review the situation,” he said on May 15, 1989.

They did not. The doctor stayed on.

From Indianapolis, Dr. Moon said he had 1,400 signatures on an Elkhart County petition calling for Tomchik’s removal. The ISBH had taken information from an employee, Kaeser and two local residents about the situation. Nearly 20 local physicians – many from the Elkhart Clinic – signed a letter urging an end to the entire situation.

“I think the whole health board is terrible,” Moon said.

And Tomchik – again – stayed on.

On Sept. 13, 1989, following a four-hour public meeting, the state declared a lack of confidence in Elkhart County, and gave 60 days to right the ship. Problems cited were noncompliance with numerous state and federal public health codes, violations of the Open Door Law, and overall patient dissatisfaction.

County officials were angered. The appointed health board was vexed.

Council president Jack Donis said in September, “This will resolve itself. We don’t really need the ISBH in the local picture because it is a local problem.” Dr. Stanley Carr, a local health board member, said, “You just can’t walk on the ceiling … just because the state tells us to.”

And Tomchik stayed defiant: “I don’t think the (state) board has the facts to back up their allegations. They have a lot of opinions to back up their allegations. … It is clear the state has bungled its investigation.”

‘Nothing less than a tarring and feathering’

More than two-thirds of Tomchik’s employees had quit in the span of 16 months.

At the end, the doctor said the patient resisted his cure. He said the department’s biggest problem was an addiction to conflict which was fed through the years … though it was later uncovered he left behind a similar scenario of in-fighting at his previous job in Florida.

With sheriff’s officers posted in the hall and about 100 people anxiously waiting for a public meeting to begin on Oct. 11, 1989, the health board, legal counsel, and Tomchik hammered out an exit strategy behind closed doors.

The terms “will prove unsatisfactory to hardened critics, who want nothing less than a tarring and feathering of Dr. Tomchik,” said county attorney R. Gordon Lord.

Tomchik was jeered during his public remarks.

Published the afternoon after the resignation announcement, Truth reporter Tom Price wrote, “Dr. Stan Reedy warned of encroachment on health programs by elected officials. Tomchik sounded the opposite alarm, along with railings against entrenched staff, state officials, the local media, and more.”

The Truth editorial board took a sharp – and decidedly different – approach, siding with elected officials. Editorial page editor Larry Murphy also issued a stand-down call to Tomchik’s opponents.

“Kept under ceaseless attack, Dr. Tomchik wasn’t able to carry out his hopes to establish harmony between the health department and elected county government,” Murphy wrote on Oct. 12. “ … For a long time, dissidents in the health department have pressed their desires through confrontation. Most of them are now on the sidelines, and the task of rebuilding has fallen on others. …

“(Remaining staff) and a soon-to-be-named interim health officer do not deserve to be subjected to carping criticism. The opposition now owes it to everyone who requires public health services to give up this addition to conflict and permit a period of peace for rebuilding.”

The Indiana State Board of Health almost immediately dropped its concerns. The health department was moved from the critical list to stable condition.

John Bentley, in his first year as a county commissioner, was to the point after witnessing the resignation announcement: “I hope this travesty will never happen again in Elkhart County.”

No more ‘little kingdoms’

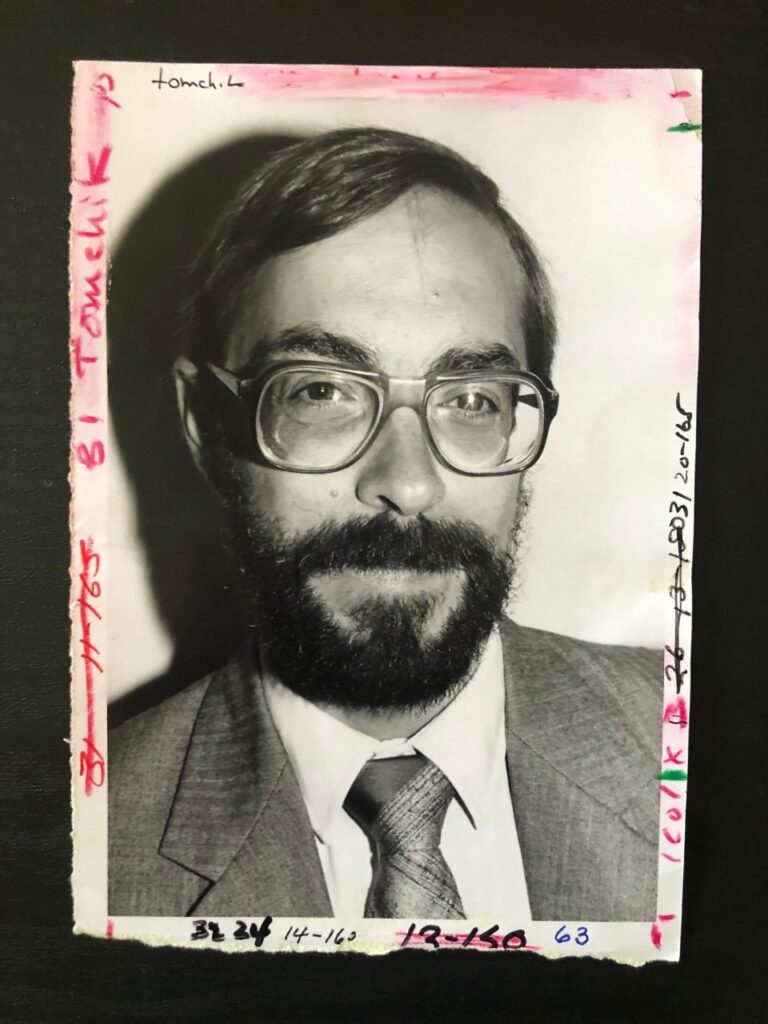

Leaving Elkhart, Tomchik became the epidemiologist in the Broward County Public Health Unit upon his return to Florida. He moved to private practice in the late ‘90s, and the dramatic headlines had no place on his curriculum vitae.

“Chief executive of agency with staff over 100 and budget of $2.1 million,” according to the document. “… Accomplishments included passage of first local groundwater protection program in the State, expansion of maternal and child health programs by 50%, coordination with EPA on management (of) a local superfund site and establishment of career ladder for professional employees. …

“Responsible for establishment of fiscal accountability and improved relationships with Board of County Commissioners, County Administrator and County Auditor.”

Dr. Frederick “Fritz” Bigler became Tomchik’s successor as local health officer. “My philosophy is that a county health department should fill in the cracks,” Bigler told the League of Women Voters in October 1990. “The people who don’t have the money are really the ones we should be taking care of. …

“Your health department is lean, it is stable, it has a healthy attitude, and it’s providing good medical care to the people of Elkhart County. “Instead of little kingdoms in each of these divisions, we now have managers that are not only competent, but are team players.”

Bigler reduced the employee count to 77 in his first year; previously, the high-water mark had been 122 employees, according to an Oct. 26, 1990, Truth report.

By 1992, the public health budget request was just shy of $2 million, with more than half to be reimbursed by the state. In 2021, the state-certified local budget amount for the department was $3.7 million.