Famous Kelby Love mural defined community response to gun violence

When a 19-year-old man died tragically in September 1993, the community’s heart began to beat with purpose.

Nearly 150 young people mourned at the funeral. Church leaders and community organizers rallied supporters for quick action. And a man created a mural that could never be bigger than his desire for peace on the streets.

John Trevor Frangis’ death marked Elkhart’s 48th fatal shooting involving teens in the span of just 20 months.

Young people were ready to stop the violence that was killing their friends. Rev. Duane Beck and artist Kelby Love were anxious to help.

The neighborhood church

“In late 20th-century America,” Elkhart Truth religion editor Tom Price wrote on June 13, 1993, “few churches still strive to serve a specific neighborhood. … (Belmont Mennonite is) making sure its neighborhood becomes a community, rather than an isolated collection of houses.”

From block parties to doorstep visits, church leaders sought opportunities to do more for residents living in the area near Studebaker Park, east of Sterling Avenue. When the time came for a building project, Belmont included a community center in the $1 million plans.

“The kingdom is much larger than our worship (service) and our congregational membership,” Rev. Duane Beck told The Truth in December 1991. “Part of being a member of the kingdom is identifying with a worship group. (But) we have to be careful that we don’t look at success or faith by how many people come through the doors on Sunday morning.”

In 1980, Belmont hired its first “community worker” to meet one-on-one with residents. The neighbors named their needs, and church volunteers helped with tasks like leaf raking and sidewalk shoveling.

“If Belmont’s community work were justified on how many people were brought into the church, probably they would not have a community worker after the first year,” Rhea Zimmerman, the third Belmont staff member to have the title, told The Truth in 1991. “The one thing that people are amazed at is that church people will come and do something for them when they don’t attend our church.”

These efforts complemented the usual missions work and student tutoring. A greater ask was coming, though, and it would require the neighborhood and the church members to become one.

Grief turns to action

John Trevor Frangis was a member of Belmont Mennonite Church. He studied at the Elkhart Area Career Center. He had many friends.

Frangis was shot once in the chest and killed at a house party on Sept. 25, 1993. Police sought charges against a 15-year-old boy who already had been to juvenile court a number of times.

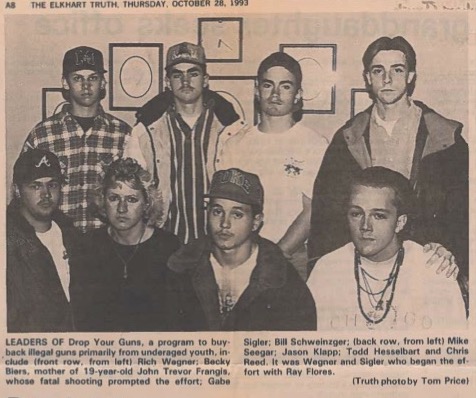

Friends and family grieved, but an idea quickly took hold. Spurred to action by Rev. Beck’s words at the service, Frangis’ mother and a number of friends created Drop Your Guns with the local Violence Intervention Project and Belmont Mennonite.

They wanted no other family to cope with such a tragic loss.

“It was really their idea for their friend,” Beck told The Truth’s Price for the Oct. 28, 1993, edition. “When they walked by the casket, I saw it on their faces.”

Less than six weeks after Frangis’ killing, the first gun buyback happened at St. John the Evangelist Episcopal Church. With a starting donation of $1,000 from area funeral home directors – and a goal to raise five times that amount – volunteers offered money to get weapons off the street.

All transactions were anonymous. Rifles were taken for $20, handguns for $40.

Within three months, the group said it had collected 166 guns. South Bend and other communities sought similar programs after seeing Elkhart’s success.

“I want to save any other mother from having to go through the same hell I go through every day I wake up,” said Becky Biers, Frangis’ mother, in an October 1993 article. “This was one way for me to vent my anger for this. … It also makes me feel like I’m not quite so alone.”

A labor of Love

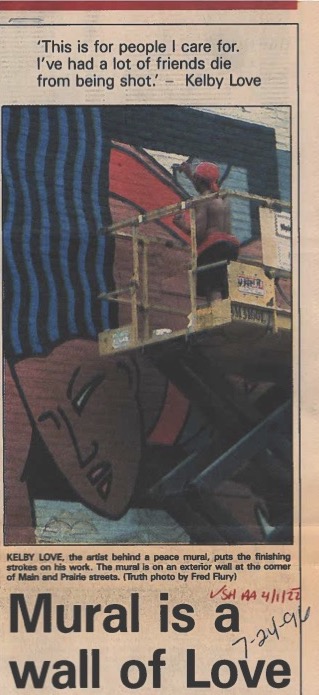

One of Elkhart’s most talented sons worked tirelessly during a pleasant stretch of weather in July 1996. Kelby Love needed to create a legacy work of art.

“(H)is most personal piece of work is taking shape on a brick wall in the city’s south side,” Truth reporter Terry T. Mark wrote on July 24, 1996. “With about 30 teen-agers at his side, Kelby Love has labored the last week to produce a vivid, anti-violence message at the northwest corner of Main and Prairie streets, an often rough-edged area marred by drug deals.”

The artist drew inspiration from the work of the Violence Intervention Project, a partner in Drop Your Guns. VIP designed the HELP program – Helping Elkhart Thru Little People – to allow youth leaders to develop anti-violence messaging and activities.

Using grant dollars from city government, Love brought his hope, faith and passion to the exterior brick of the Louie and Kelly Bar. The iconic mural speaks to his dream for the values of his community – faith, family, togetherness.

“I like to produce positive images about the community. I think this will get a better image for the community,” Love told the reporter. “This is for people I care for. I’ve had a lot of friends die from being shot.”

Love incorporated the Violence Intervention Project’s logo in the work, though the group dissolved just a year later. The artist also included symbols supporting education and tolerance.

He didn’t sign his work. He didn’t need to.

Legacy

Kelby Love took pride that the mural’s message was still relevant two decades later, and it wasn’t lost on him that the paint hadn’t faded and the wall was graffiti free.

“No one has touched it,” he said in The Truth on Aug. 6, 2013, “because everybody knows who did it. It was this community.”

Love died at the age of 58 in 2018. As the mural approached its 25th anniversary, its future came into question. Other outdoor works by the artist gave way to redevelopment, and the corner of Main and Prairie is next.

In December 2019, Kelby Love’s mother, Glenda, pleaded with the Elkhart Redevelopment Commission to save the mural.

“It is the only legacy that the city has of his,” she said. “He has given so much to the city of Elkhart. … I think the city owes this to the black community. The black community in Elkhart doesn’t get the privilege of being recognized.”

On Sept. 8, 2020, the city commission purchased the building from the Fort Wayne-South Bend Catholic Diocese. The purchase price was $7,050.

Redevelopment member Sandi Schreiber told a Truth reporter the city was “committed to saving the image” Kelby Love created out of hope for greater peace.

Demolition of the block finally began in the winter of 2023-24 after as many as three engineering firms studied whether the mural wall could be saved. In March 2024, Kelby Love’s signature was carefully cut from the mural by city workers and presented to Glenda Love. Mayor Rod Roberson announced the city would project the mural’s image onto a wall at the site when it is redeveloped.