Looming over downtown, the costly Arch was toppled by critics

Downtown Elkhart’s unique monument towered above Main Street at just 26 feet.

Merchants rushed to congratulate each other almost as quickly as they had written the checks needed for its construction.

Labor unions volunteered for the heavy lifting. Civic groups gathered help for decorating.

The Elkhart Truth printed supportive words with lyrical photo captions and frequent news updates.

The Arch was designed to support six tons of decorations and all the weather that could be brought down upon its steel beams. But it couldn’t hold up against criticism. Built for the city’s Christmas tree, it was intended to bring the holiday closer to the city’s residents.

That joyous spirit faded fast.

By the time it was dismantled less than five years later, the Arch was a costly, green and gangly lightning rod of attention at the center of downtown Elkhart. It may have cost as much as $33,000 to actually build it – a quarter-million in today’s dollars – but just $990 on a city contract to have it hauled away.

Chorus of commentators

“The so-called ‘Archy Picasso’ of Elkhart is not art, but just a mess of girders that stirs crude jokes by visitors. … However it may be decorated or camouflaged, Elkhart’s downtown arch remains an ungainly, awkward, ugly thing,” The Truth wrote in its Nov. 13, 1967, editorial. “… It is hard to imagine anything more inappropriate than such a display at Main and Franklin for the image of a modern progressive community which the heart of downtown Elkhart ought to project.”

By its fifth and final winter, the Arch had lifted up decorated evergreens each December as originally planned, along with a cross on two observances of Easter. It served as a perch for a mobile home at least once, and held aloft a flag on occasion.

Supporters and critics alike said it should have been used more. Usually unadorned, the structure loomed quietly over downtown.

“You know, I came to Elkhart in 1965 and no one would tell me what it was or who put it there. They acted ashamed of it,” Graham Howard, a local Boy Scouts director, told The Truth for a Sept. 28, 1967, article.

Elkhart Police Patrolman Lester Clark told everybody it was the “largest Christmas tree stand in the world.” Allen Naden said, “If one traffic light were hung from its center, it’d at least be functional year-round.”

Maria Stegenga, a resident in the 300 block of West Franklin, said the Arch was useful. It gave her family and friends an unmistakable landmark where they needed to turn and find her house.

Nelson Sorg of Sorg Jewelers, located at the time just steps south of the Arch, said, “It was beautiful at Christmas and during trailer shows. It has good advertising potential and should have been used more. But as it is now – bare – it’s a monstrosity!”

Still more offered hot takes on the street – they were dubbed the “anonymous group of advertisers” by a wry reporter, Judy Baer. Some suggested the Arch should have been formally named, depicted on matchbooks, and memorialized with tchotchkes “like New York does for the Statue of Liberty.”

This intersection of ideas was lightyears from the same patch of ground where a young man thought up a simple, poignant idea.

Uncommon and costly ground

Jim Cooke, working at First National Bank on a summer break from Indiana University, talked with a few store owners. He wanted to see more Christmas spirit displayed on the streets.

“Several local merchants were so impressed with the plan that they contributed the thousands of dollars needed to erect a steel superstructure for the tree to stand on,” Bonnie Biemer reported in The Truth’s Oct. 16, 1963 edition.

Walter G. Krumwiede Jr. of Ziesel’s Department Store was president of the Downtown Elkhart Association. “Elkhart needs more people like Jim Cooke, people who are interested in improving and beautifying downtown Elkhart,” he said.

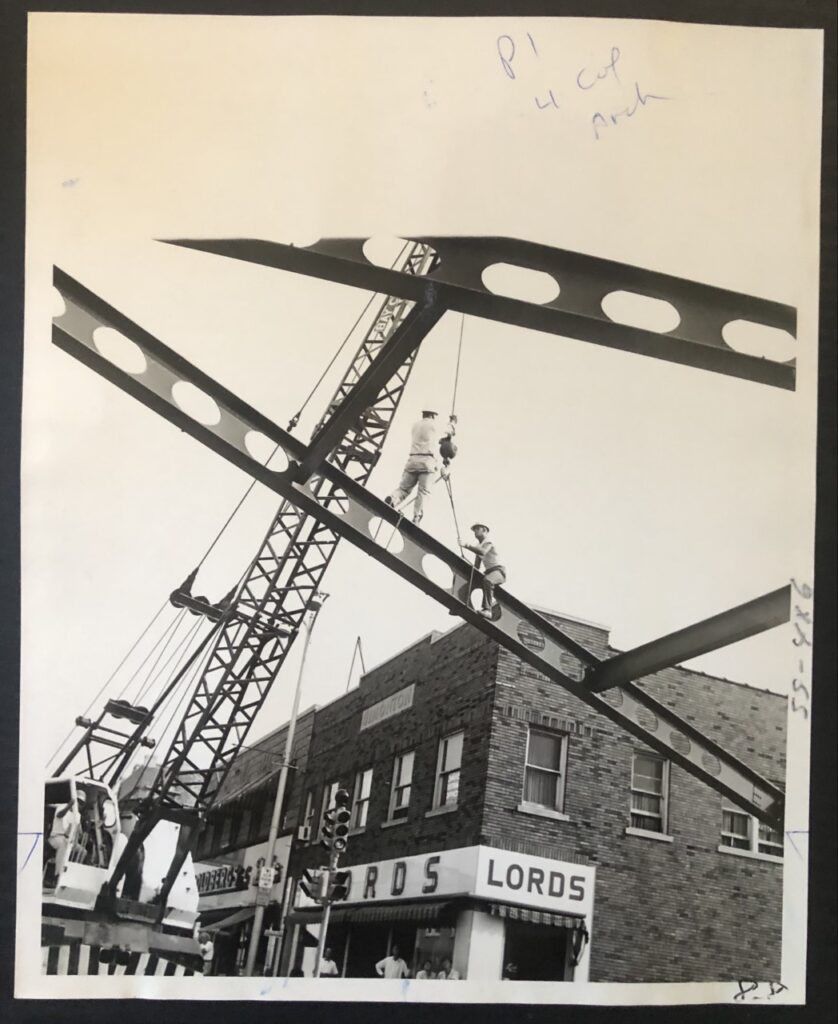

The plans were carefully drawn and approved. The supports were to be placed 30 feet from the intersection down Franklin to not interfere with traffic sightlines. The whole thing was intended to be removable and used only for special occasions.

Then, they started digging.

On the Ziesel’s corner, contractors ran into an old manhole, requiring them to go an additional 5-7 feet deeper. Also, the architect recommended more substantial foundations and the addition of steel rods under the street to connect the footings and prevent spreading.

The intersection pavement needed to be dug up. The costs were rising by the hour. Merchants never spoke of the final price of construction, but Krumwiede admitted years later a guess of $10,000 would have been “conservative.”

“Despite discouraging setbacks,” The Truth reported Nov. 19, 1963, “the Downtown Elkhart Association pushed today toward realization of its plans for a colossus Christmas tree for Elkhart, to be completed by the end of the first week of December.”

They made the deadline. Iron Workers Union Local 292 and Operating Engineers of Local 150 gave their time working into the night. The Jaycees organized volunteers to decorate.

On Dec. 5, 1963, in freezing temperatures, the first Christmas tree was placed atop the downtown Arch. A blue spruce topped by a star reached five stories high. It was decked in 700 lights, tinsel, and ornaments.

Two weeks later, at a merchants meeting, Krumwiede read congratulatory letters about the tree. Others attending spoke about the pride residents felt and of the out-of-towners who had come to see it.

Due to construction changes, the Arch was now permanent. But long-range ideas and upkeep were not considered. By Christmas 1965, the city’s electrical department had taken on the tree decorating duties from volunteers.

The Truth made no note of any bubbling concern in its coverage the first few years. Instead, photographers documented stories of the tree donors and installers.

One 1965 photo was captioned, “Would you believe it? This photo was taken from a seat in Santa’s sleigh. The old gentleman was making an emergency trip back to the Pole, so that the latest orders from Elkhart area boys and girls could be placed in time for Christmas. The night view of the downtown Christmas tree shows its shiny holiday accessories to best advantage.”

Less than two years later, the merchants moved unanimously to sell the “iron monster,” as some in the community had started calling it. Liability insurance alone cost the business group more than $900 a year.

Just like a used car, the owners said the price was negotiable and immediate possession was expected.

Dreams in spotlights …

At least a few people in the community, though, were beginning to generate ideas to save the Arch and make it useful.

Jim Brubaker, WSJV-TV art director, offered his cynical view to reporter Judy Baer about the Arch: “Perhaps the city could combine two controversies by lowering it into the St. Joseph River to begin the talked-about bridge at Bulldog Crossing.”

Meanwhile, Brubaker’s father was getting a serious idea down on paper.

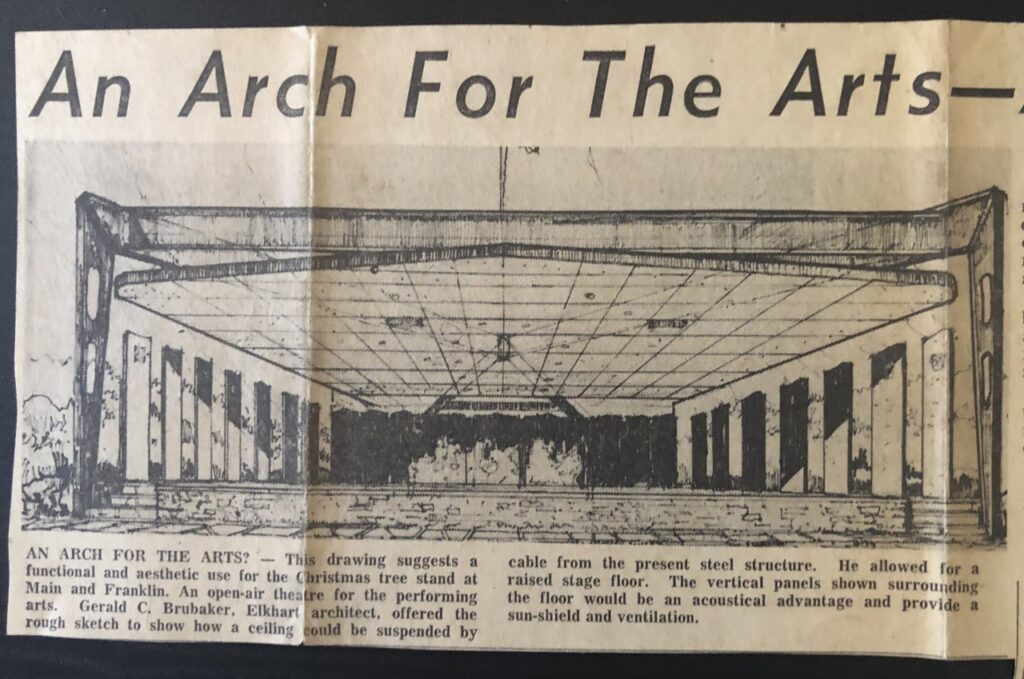

It’s not clear if anybody ever considered architect Gerald C. Brubaker’s drawing of the Arch as an outdoor performing arts center. After all, the article ran on page 17 of The Truth’s Oct. 6, 1967, edition, and no follow up appears to have been written.

Brubaker envisioned the structure relocated to a park. A ceiling would be suspended from its cross beams, and vertical panels on the sides would add acoustical value and shielding from the sun. The open-air theater with a raised stage would have had one fixed wall, behind which dressing rooms and concessions could have been rolled in or built.

“This would fit into the city’s goal of building a band shell,” Baer wrote. “… Brubaker sees no aesthetic value in the structure the way it stands now, but to paint it or decorate it in the downtown area would be increasing the problem it already presents, he feels.”

Brubaker offered no cost estimates for relocation or construction.

… and canary yellow

One city official was dreaming up ideas of his own. Merchants began actively looking to sell or give away the structure starting in September 1967. Parks superintendent Wesley Krey approached his board less than 60 days later with a plan.

It wasn’t a good one, in the eyes of the park board and city council.

Krey estimated the parks would spend a minimum of $5,000 annually to keep the Arch at its original location. He would paint it canary yellow, add theatre marquee lights, and decorate it monthly.

Paul Thomas, the council’s representative to the parks, said diplomatically, “(The Arch) does cause people to talk about and remember Elkhart,” adding the park board “would have to remember the arch now belonged to the taxpayers more than before,” if acquired.

Pauline Greenleaf, Mayor John Weaver’s personal representative to the park board, didn’t mince words: Take down the Arch. The park board officially said no thanks to the merchants on Nov. 22, 1967, due to “unwarranted substantial expense.”

A path forward

On July 16, 1968, The Truth’s headline declared: “Downtown Arch Has A New Owner – Us!”

The Elkhart Board of Works accepted ownership of the structure, and estimated the value of the steel alone at $10,000 to $12,000.

But the Arch wasn’t headed to the scrap heap. Mayor Weaver, a civil engineer, actively pursued a plan to study its relocation to Nappanee Street as a pedestrian overpass between Mary Daly Elementary and West Side Middle School, which became reality about three years later in 1971.

The Arch came down Aug. 7, 1968. General Crane Services was paid $990 – the city council, of course, offered its opinion the price should have been half that much. Crews dismantled the structure and carted it to the street department for storage.

Moments after the last piece was taken down, resident Don Rospopo told a Truth reporter, “It’s strange without it. It was a waste of time and money to put it up in the beginning and now to take it down. I would like to have seen it stay up and the city do something with it.”

Two months later in 1968, the merchants asked permission to place Christmas decorations over the intersection of Main and Franklin. Under the headline, “Arch Gone But Not Forgotten,” The Truth reported, “City officials said they want more information before making a decision.”