Civic Plaza met the moment. Is its time fading?

When the land met the demand, Civic Plaza finally became a dream fulfilled for city leaders.

The Main Street gathering point certainly has provided successes and challenges since first developing in the late 1980s. The looming clock tower and the often-dry fountain have been the backdrop for decades of community memories.

Now, the writing of its final chapter starts. Civic Plaza was talked about for 65 years, but may end up being used for only 35 or so.

A proposed outdoor concert venue at the heart of downtown Elkhart would bring more change to a city block with a rich history.

A plan with no land

John Nolen floated the idea for a large meeting place in downtown Elkhart when he wrote the original city plan in 1923.

“The need of at least one open block in the central section of cities is, or ought to be, obvious,” Nolen wrote 65 years before reporter Nevin Dulabaum reshared it in a November 1988 article. “Under any proper conception of civic life, it is really as necessary in many ways as a municipal building.”

But storefronts filled Main Street through the middle of the 20th century. Templin’s music store, Montgomery Ward, Goldburg’s store for men, jeweler Claude Shinneman, and W.W. Wilt’s took up the core of the 300 block of South Main Street.

Those stores and more were “flanked on opposite corners by downtown merchant giants Ziesel Bros. and Chas. S. Drake,” legendary reporter Arden Erickson wrote in December 1989. “… Once upon a time, a shopper could come to downtown Elkhart and, in just one block, find a goodly number of retail establishments.”

The memorable and ill-fated Arch found a home for a while at the southern end of the block as a 1960s attraction. The structure became the opening chapter of a sad story. By the end of the 1970s, nearly 30 storefronts on Main were empty. The next chapter, the Midway Motor Lodge, barely made it to 1990 before its bankruptcy.

It was time for a fresh idea.

Downtown ‘doesn’t have a heart’

In 1987, Jim Perron was chasing something that had eluded Elkhart mayors for 20 years: re-election. “Too many administrations have been voted out after one term to lend the city any continuity,” he said to Truth reporter Brian Howey in October.

Perron charged through his first four years in office with aggressive plans to “Rebuild Elkhart.” With the development of his Phoenix Program, downtown became a critical area of concern. Balancing public funds with private donations, a $900,000 plaza was proposed for the city’s center.

Howey wrote Civic Plaza was the “symbolic issue of the campaign.”

“It’s designed to bring more people to the downtown,” Perron said after he won the vote for a second term. “It was felt very strongly … that there was a need for a focal point in the community – a place where the community could have identity.”

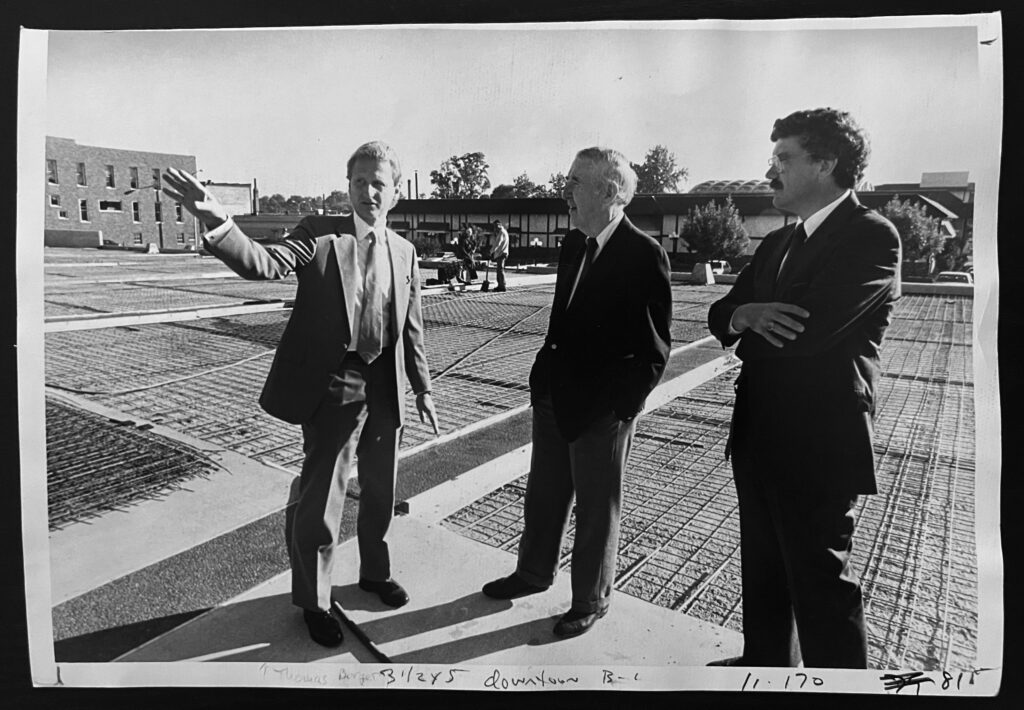

Working from an office inside Seifert Drug, Ball State University architects put ideas on paper. A small public meeting for 30 took place at the Midway Motor Lodge to review the work.

“The thing that we were told is that downtown was a pit,” said BSU professor Harry Eggink, an Elkhart native. “It doesn’t have a heart. There is nothing that identifies itself to downtown.”

The early drawings closely mirrored the finished product. Intended to provide space for farmers markets and New Year’s Eve celebrations, the 365-foot-wide deck would have a clock tower. Colorful flags would wave over a fountain and tables.

“This has to be a very multifunctional place,” said Tony Costello, another Ball State architect. “It has to accommodate the solitary person there at 7:45 in the morning sipping a cup of coffee. It has to be there for Memorial Day to be the major reviewing stand for the parade coming down Main Street.”

Supporters and critics

With 570 balloons released into the air in celebration, the mayor stood near Main Street on March 3, 1988, and announced, “As a central focal point for our city’s future activities, the civic plaza will allow all the citizens of Elkhart to come together to celebrate our sense of community.”

The Perron administration never ran short of ideas … or critics.

Phil Stiver, an Elkhart City Councilman, told Truth reporter Alicia Dean that day, “The project has certainly not been without controversy. What we have seen is a rallying around this project that seemed to be without substance at first.”

Corporate donations took the steam out of some arguments. The Truth’s editorial board, instead, called out designers. The request? A vibrant setting to counter the close-by buildings with dark-tinted windows.

“(A) note of cheer appeared. The new (plaza) sign was brightly topped off with a little red peak. That’s a nice touch. There should be more color,” The Truth editorial stated on July 18, 1988. “The plaza is supposed to be a festive place for fun and celebration. The surrounding buildings don’t give much help in creating that feeling. Plaza planners, please compensate as best you can. Don’t be stingy. Put in lots of color!”

Short of the goal

Miles Laboratories and Coachmen Industries were the first corporate contributors to the Phoenix fund for Civic Plaza. First National Bank later put in $100,000 toward the clock tower. The timeline put construction in 1989.

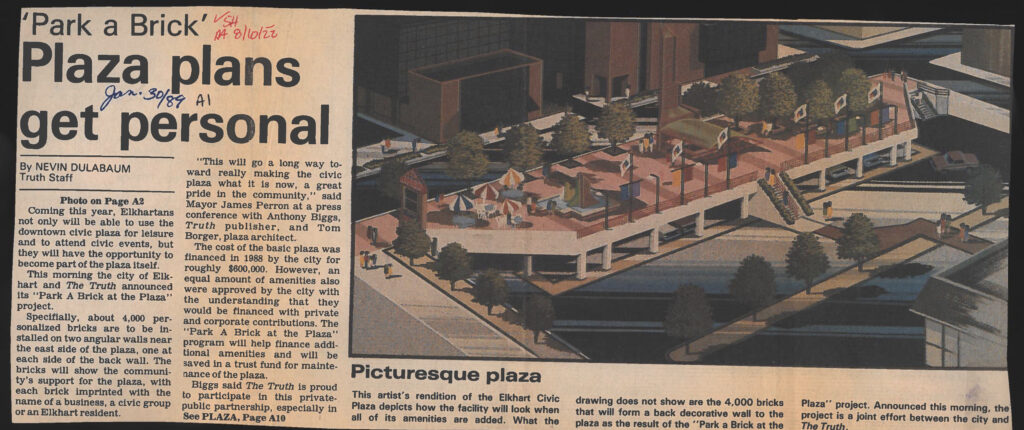

Celebrating its 100th year of publishing, The Elkhart Truth announced a program in January 1989 to “Park a Brick on the Plaza.” Ron Schmanske, the newspaper’s marketing director, said 4,000 inscribed bricks would be for sale. Additional amenities and a long-term maintenance trust would benefit from the sale.

The public purchased just about 1,000 bricks by December 1989. The total sold came in at just about 1,500 as the program push ended in November 1991.

It wasn’t the only effort coming up short on its promise.

Troubled waters

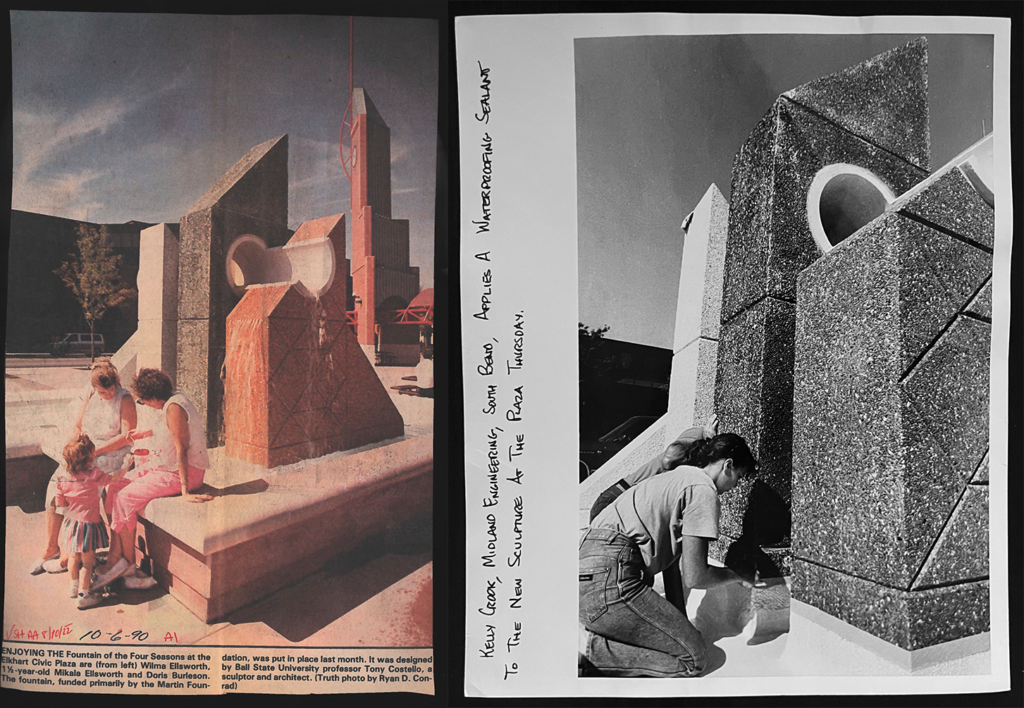

The fountain designed by Costello, one of the original Ball State architects drawing the Civic Plaza plans, took shape in September 1990. “He said the beauty of any abstract sculpture is that the viewer makes it what they want it to be,” Truth reporter Stephanie Davis Gattman wrote. “The Fountain of the Four Seasons could be sails in the wind to some, but to a child it could be building blocks.”

Costello designed the four triangular slabs of aggregate for water to “fall off the apex of the triangle. … (In winter it would) form a cascading icicle through the natural freeze and thaw.”

A crane nearly tipped over trying to place the biggest piece, weighing in at a hefty 8 tons. The structure required a complex plumbing and filtration system. A $50,000 grant from the Martin Foundation covered about two-thirds of the cost.

“It’s like putting together a small building,” said architect Jeff Helman of Borger Jones Leedy. “… We all have taken this as a labor of love.”

Less than a year later, city engineer Gary Gilot said the fountain was out of service due to grouting and water-proofing issues. A rubber lining on the fountain floor needed repairs in the summer of 1992. The Fountain of the Four Seasons was becoming more sculpture than fountain.

Decades later, the problems persisted.

“It’s in disarray,” said Mike Lightner, director of the city’s maintenance department, in a 2014 Truth report on why the fountain wasn’t running. “There are a lot of things wrong with it; there are cosmetic problems with it, and there are also plumbing problems with it. We’ve been mending it together for years to make it work.”

Coming alive

Civic Plaza wasn’t quite ready for the 1988 Elkhart Jazz Festival.

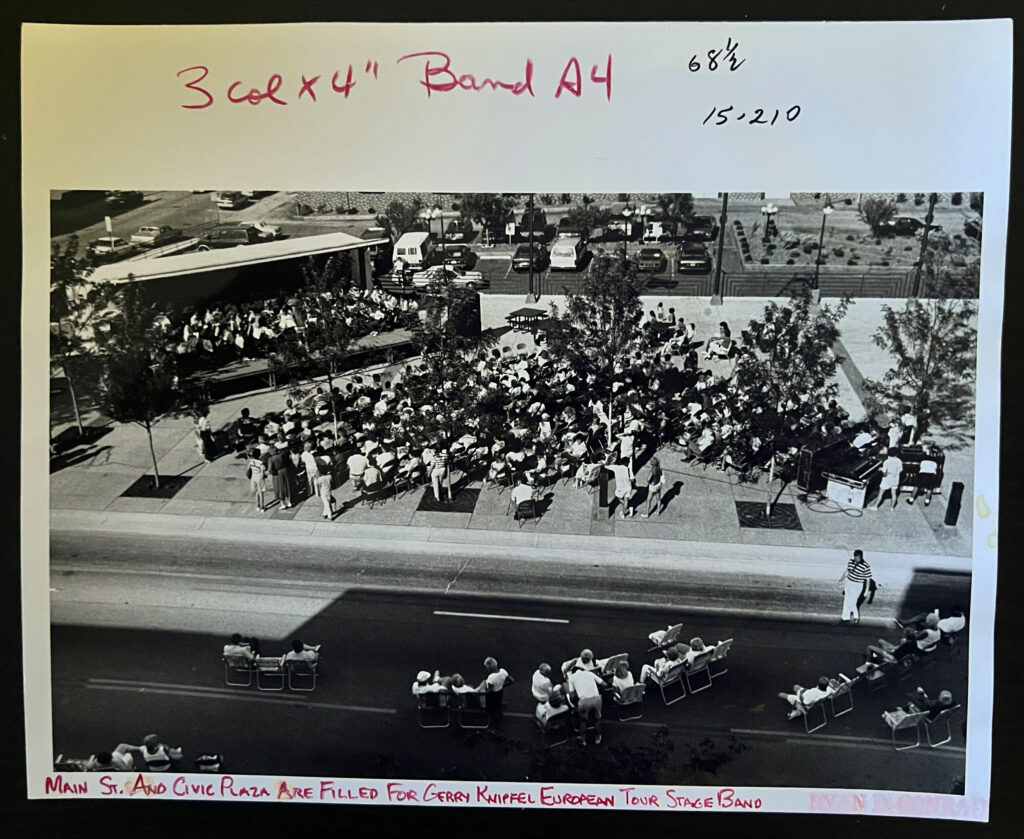

When the block finally opened, though, residents didn’t hesitate to check it out and offer up their own ideas for uses.

Jay Krull launched his hot-air balloon from the plaza. Vern Wamsley offered up his antique cars for a weekend showcase. A downtown group planned lunchtime entertainment.

“I like to see people using the downtown again,” said resident Mitzi Sipe, one of a hundred or so who brought lawn chairs and lunches to see the Larry Dwyer Trio perform in August 1989. “It’s like it’s coming back to life again.”

Maribeth Hicks, the city controller, said, “See, it is more than just a slab of concrete.”

State officials felt the same. Lt. Gov. Frank O’Bannon presented the Indiana Main Street Program’s best downtown design award to the Elkhart Centre organization.

Lifting up spirits

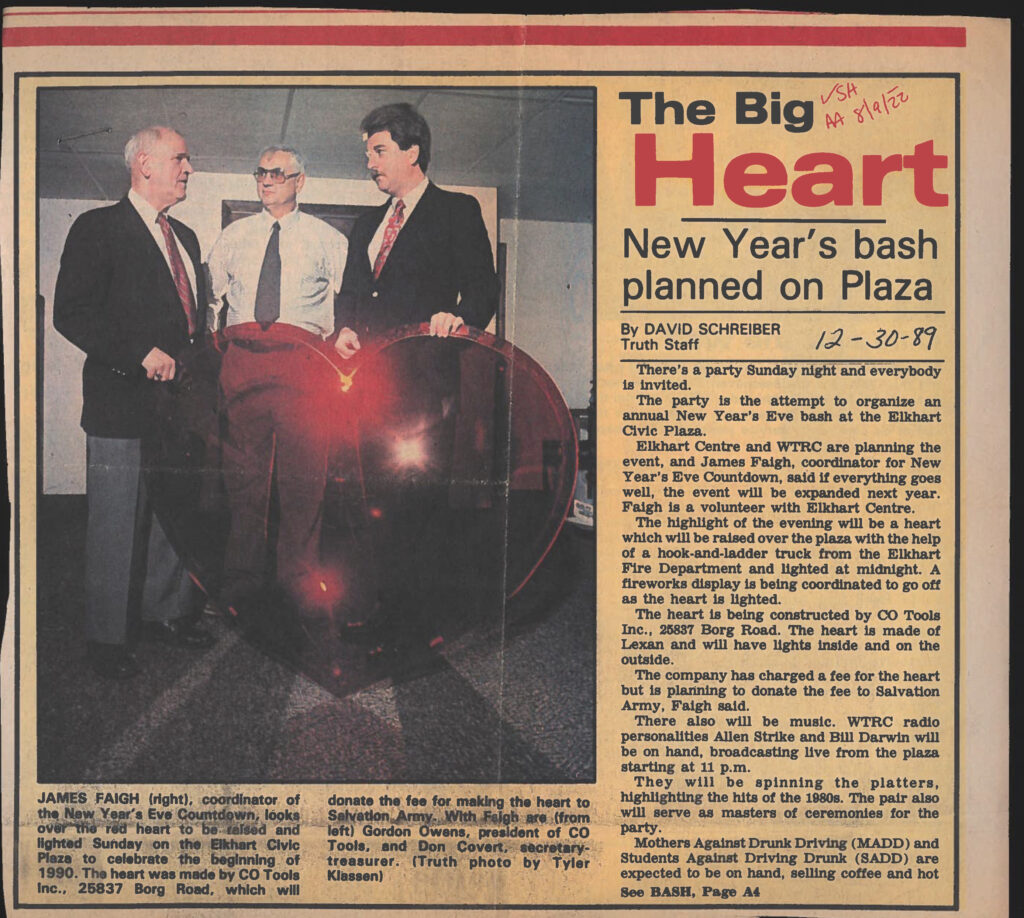

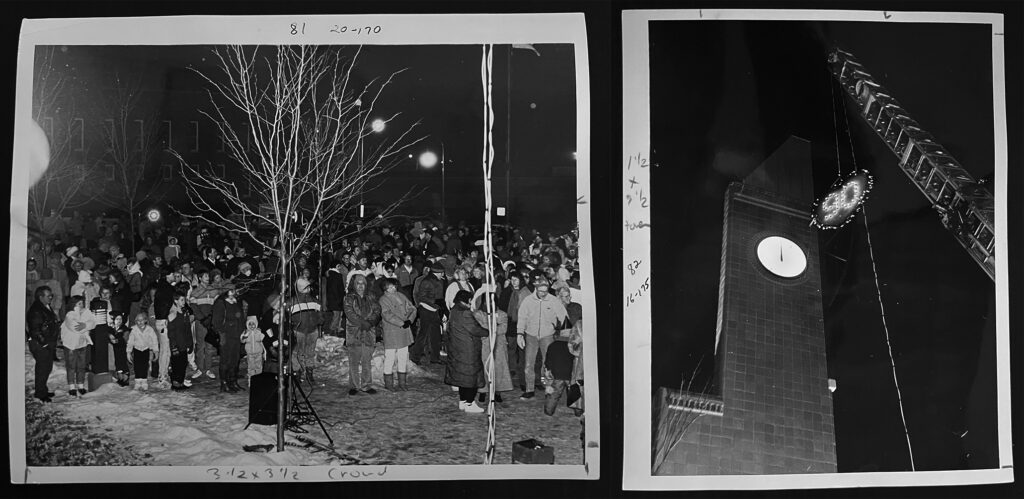

When the clock tower was finished, Jim Faigh saw opportunity, too.

On New Year’s Eve with the help of fire department’s hook and ladder crew, Faigh raised the lighted polycarbonate heart to ring in 1990. Allen Strike and Bill Darwin broadcast live on WTRC-AM and played the hits of the 1980s for the festive crowd.

Into the ’90s and early 2000s, Civic Plaza became the meet-up spot for parades, festivals, rallies, protests and cultural celebrations. Nearby, though, ideas for a convention center never materialized and the Elco Theater was on the decline.

Unwanted nighttime activity was a problem. In August 1990, Paul Thomas told the Elkhart Urban Enterprise Association board about vandalism and suggested Civic Plaza “close” at 11 p.m. like the parks. Stephanie Davis Gattman reported Thomas telling the group “many people are appalled at the crowds congregating there during the evening.”

Daytime hours presented challenges, too.

“We could use a little more shade,” Tina Ulrich, an Elkhart Public Library employee, told Truth reporter Nancy Bounds during one sunny and steamy summer lunchtime concert.

Holding off development

In 2008, Perron called his administration’s Civic Plaza accomplishment “an icon for the community.” That same year, Democrat Mayor Dick Moore committed the city to a greenspace between the Main Street plaza and Waterfall Drive.

A decade before, the city had paid about $1 million to purchase and tear down the hotel behind the plaza. In 2003, a developer suggested 150 or more apartments on the site. A few years later, another company suggested condominiums.

“The people told me yesterday they wanted their central park. That will be our park. No buildings on that space,” Moore told The Truth following a festival marking 150 years since Elkhart’s founding.

The lawn appealed to those seeking a break from Civic Plaza’s hard edges. Both Moore and his successor, Tim Neese, touted the frequency and creativity of events filling the entire block.

In 2018, a developer with eyes on a multimillion-dollar office building asked about the plaza’s availability. City leaders declined. In fact, a concept drawn up later in the year called for expanding the street-level deck as part of other park improvements like a stage and public restrooms.

“The Central Plaza is a prominent civic gathering place located in the heart of downtown Elkhart,” Neese said in a Truth report on Nov. 13, 2018. “The space currently functions adequately … (but) in order to create this vibrant destination, it must reflect the character of our community, and it is critical that the public be involved in the process.”

Coming attractions?

City leaders and financial backers unveiled the proposed Elkhart Amphitheater in April 2023. The private-public partnership announced Elkhart could attract nationally touring bands to an open-air venue with up to 8,000 seats. The inscribed bricks on the Civic Plaza wall, along with the other memorials added in the past 35 years, were to be relocated and incorporated into the venue’s design, according to developers.

By March 2024, though, the deal with private investors fell apart. Mayor Rod Roberson said his administration would seek other partners “enhancing Elkhart’s reputation as a live music destination.”