Ben Barnes ‘was second to none, but never better than anyone else’

When Ben Barnes finally took a knockout blow – a sucker punch to a life that couldn’t be beat – the entire Elkhart community cried. The tears were raw, real, nonpartisan and color blind.

The man with the generous hands and giving smile was always just bein’ himself.

Black.

Bursting with pride for the south side.

A powerful presence in every room.

Equal parts demanding and caring.

Quick to lend a hand and share a meaningful lesson.

Ben Barnes was a winner for all his 71 full years. And, just as his father taught him, he never considered himself better than anyone else.

Family is community

Big Syl and Lura Mae Barnes raised a lot of good kids.

Sam gave his life serving his country in Korea. Erich was a star defensive back and played in an NFL championship game and six Pro Bowls. Lester joined the clergy, and he and Sylvester Jr. carried on the family trade as plasterers.

And that doesn’t even account for half of the family that grew up on Chapman Avenue.

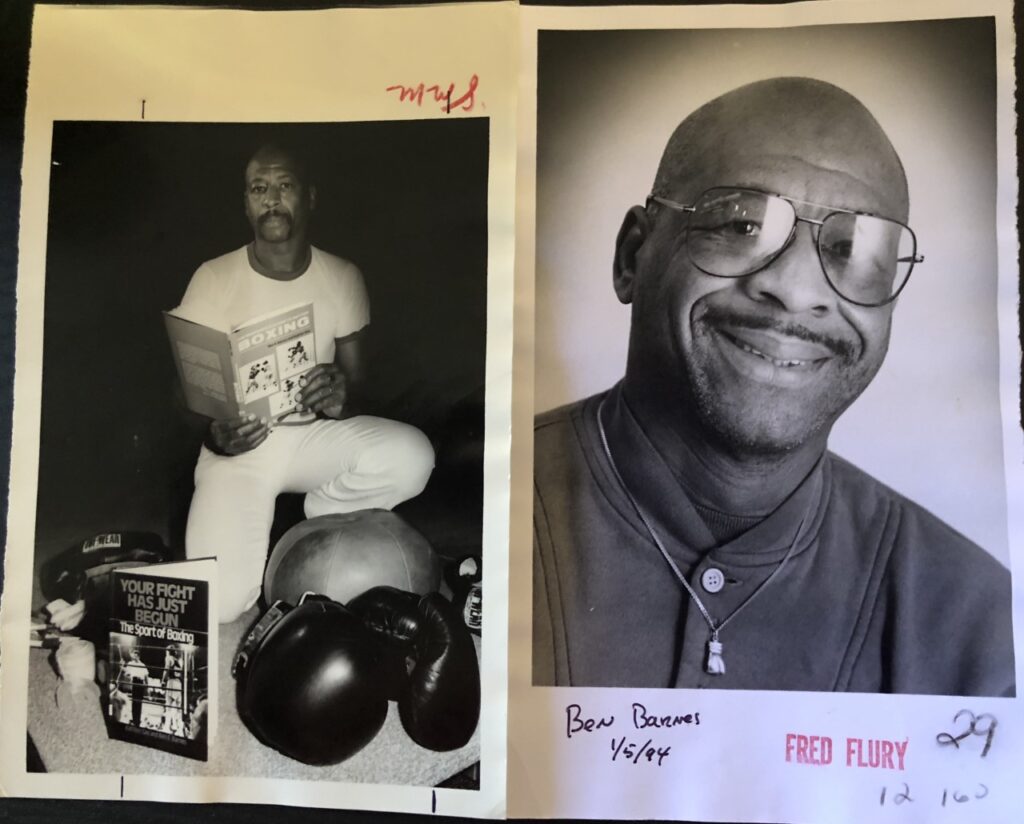

Ben Barnes went to Ullery School, St. Vincent’s and Elkhart High, and he was Indiana’s amateur middleweight boxing champ in the late 1950s. He worked for NIPSCO and “threw mud” on the side in the Barnes Sons contracting business.

When he was 29, he put down his own roots at 1017 W. Indiana and began making an indelible mark on his hometown. He joined the Urban League, a local group very active in leading community discussions amid racial tensions in the late 1960s. He started his youth outreach by creating the St. James Boxing Club. He co-authored three books. He ran for local office.

With all of these activities, Ben Barnes deposited 100 percent of himself and always dispensed the wisdom of Big Syl and Lura Mae.

‘His joy of livin’ ’

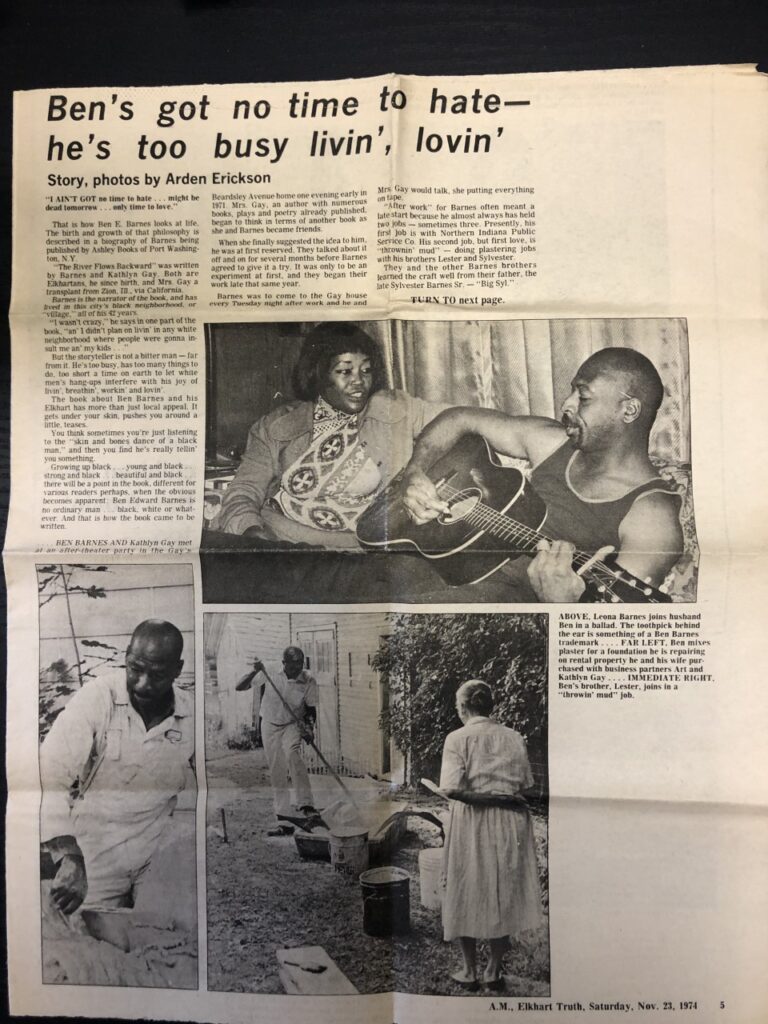

“‘I ain’t got no time to hate … might be dead tomorrow … only time to love,’” is how Arden Erickson opened his feature about Barnes in the Nov. 23, 1974, Elkhart Truth A.M. Magazine. “But the storyteller is not a bitter man – far from it. He’s too busy, has too many things to do, too short a time on earth to let white men’s hang-ups interfere with his joy of livin’, breathin’, workin’ and lovin’.”

Barnes had just been elected weeks earlier to the Elkhart County Council, the first Black man to win a seat in county government. He also was close to releasing “The River Flows Backward,” a memoir coaxed from him by fellow author Kathyln Gay.

“‘The River Flows Backward’ is a talkin’ book,” Erickson wrote, “the father talking to his sons and daughters, the mother talking and singing to her God as she works in the house, the father and sons talking, singing and telling stories as they do a plastering job, talking to the girls, the dudes on the job, or with friends at the Cozy Corner.

“… and sometimes talking to a dead brother who still walks down the street with you on a rainy night when there just is no one else who can hear and understand the same way.”

Erickson was a legendary writer who never interrupted the conversation between his subject and the reader.

He wrote, “Verbalism is a great part of black culture, the keystone and lifeblood of the village. Except for a few reflections and comments by the other author … Barnes talks his way all through ‘The River Flows Backward.’ … The book about Ben Barnes and his Elkhart has more than just local appeal. It gets under your skin, pushes you around a little, teases.”

After the book was published, the authors made television appearances throughout the region and were honored for their contributions at the Indiana University Black Culture Center on April 21, 1975. They were nominated for a National Book Award.

Still on the shelves at Elkhart Public Library, “The River Flows Backward” is both raw and inspiring. Barnes wrote in it, “(A man) has to figure out how to love his own dumb ass stumblin’ self before he can share with anyone else. I could only be free if I loved the n—– in me and nobody better dare say a word about my bravery ‘cause I was gonna fight to keep alive and find a place for that n—– I was learnin’ to love.”

In his review, Erickson wrote, “Big Syl pounded, sometimes physically, black awareness and pride into his children before the terms became chic. One of his essential messages to the children, Barnes says, was that they were second to none, but never better than anyone else.”

‘The man with the fu manchu’

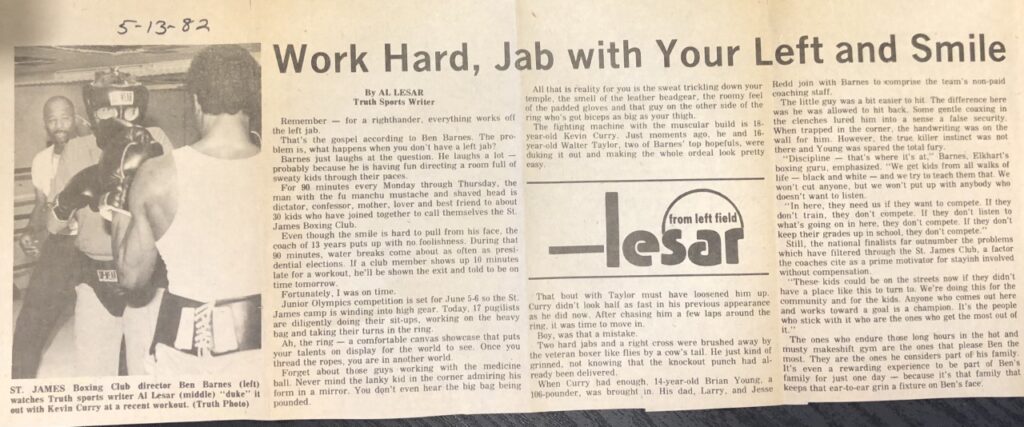

“Water breaks come about as often as presidential elections,” sportswriter Al Lesar wrote about St. James Boxing Club practices in a Truth column published in May 1982. “If a club member shows up 10 minutes late for a workout, he’ll be shown the exit and told to be on time tomorrow. …

“For about 90 minutes every Monday through Thursday, the man with the fu manchu mustache and shaved head is dictator, confessor, mother, lover and best friend to about 30 kids who have joined together to call themselves the St. James Boxing Club.”

Starting about 1970, Barnes got kids off the street to teach them skills and discipline. More than 30 years later, city councilman Arvis Dawson told The Truth, “Ben saved so many young kids with that boxing club. He gave them an avenue to vent some of their frustration.”

And Barnes himself said his passion for developing young talent was actually a savings for taxpayers. He often said it cost about $42,000 on average to incarcerate someone.

On the third floor of the old St. James Church, Barnes’ brand of strict rules and high spirits caught on.

“Discipline – that’s where it’s at,” Barnes told Lesar that night in 1982. “We get kids from all walks of life – black and white – and we try to teach them that. We won’t cut anyone, but we won’t put up with anybody who doesn’t want to listen.”

After more than 16 years running the club, he just wished for one thing: the money to be able to do the work full time and touch even more lives.

“Some of these kids had never even slept in a clean bed,” Barnes said in December 1986. “When I’ve got them out on the road to work and to box, I want them to stay someplace that will give them something to think about. I’ve heard some of the kids say, ‘Wow, when I grow up, this is the way I want to live.’”

His powerful message transcended athletics. He told stories about discrimination he faced when he was young – the hotels where he couldn’t stay, the yards where he saw burned crosses.

To a group of Central High School students in May 1983, Barnes said, “When I woke up in the morning, I knew I had a step to take, to fight the elements out there. … They say, ‘You can’t make it in the white man’s world.’ I don’t believe them. I don’t consider this a white man’s world.”

A seat at the table

Leroy Robinson and John Coley just wanted to run a Black person for county office. The Urban League members turned to Barnes as their hopeful.

Ben wanted them to know something.

“I said, ‘Fellas, if I run I’m going to run to win. I don’t want to run just because I’m black,” Barnes told Truth reporter Dave Overton for a Dec. 21, 1986, feature. “So when I ran for office, I didn’t run as just a black. I’m hoping that when people voted for me, they voted for me … not for the color of my skin, but for what I stood for. I am an individual who believes in working for my constituents as a whole.”

Barnes won that District 2 race in 1974, and then again in 1978 and ‘82. He reclaimed the seat for a fourth term in 1990. Through most of 16 years of county council meetings, he was not only the one person sitting at the front of the room who was Black – he was the only Democrat in the room, too.

And he still found room to work. Upon his first farewell from the council in 1986, he mentioned friends he had enjoyed governing with: George Neff, Ralph Greene, George White. “I’ve enjoyed each and every individual that I’ve worked with. Even the ones that may not have been too cool. I learned something from them,” Barnes told Overton.

Because he only knew how to give 100 percent of himself, tough votes weighed on him years later. He spent plenty of time reflecting on whether the action he took was right. When he voted against demolishing the County Home, he second-guessed himself “a million times over. …

“I’m hoping, God knows, that I did the right thing in many cases,” Barnes said. “If I didn’t, it’s just too late. But, I tried.”

‘He spent his time using what he had’

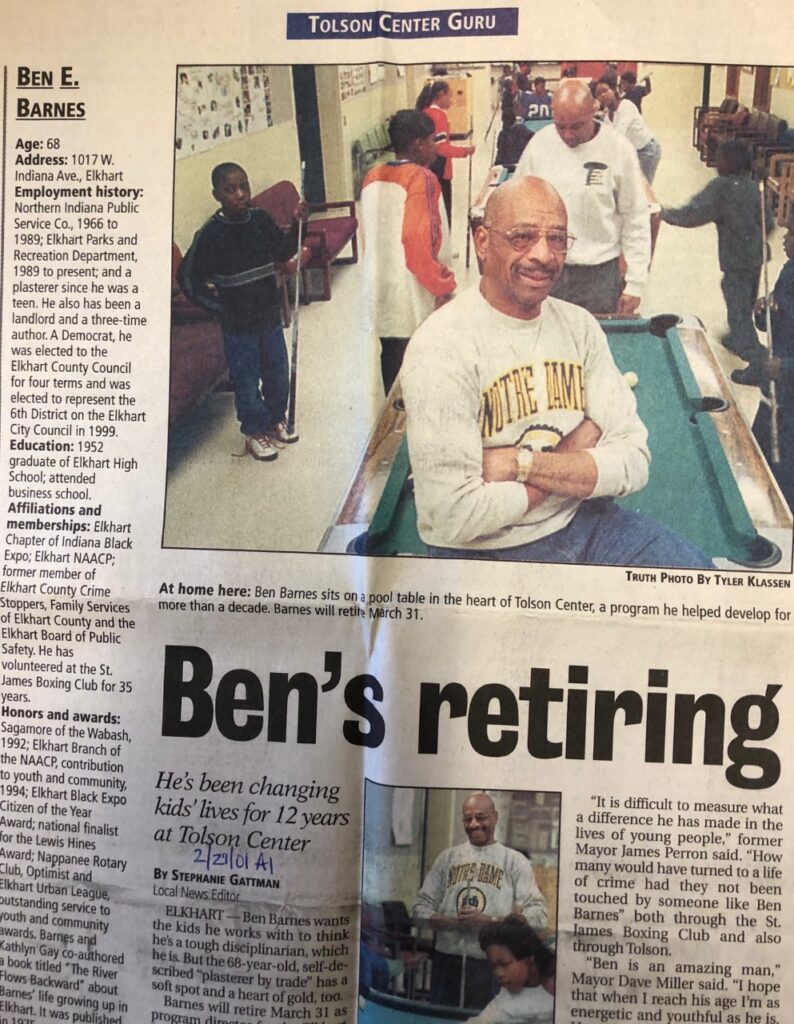

Ben Barnes returned to local government in 1989, with his appointment as the first recreation coordinator for the new Tolson Center. In 1992, Gov. Evan Bayh toured Tolson, and finished his visit by presenting Barnes with a Sagamore of the Wabash.

“Through his work with the St. James Boxing Club, he brought a lot of self-respect and discipline to the kids,” said Matt McNeile, a former city parks co-worker of Barnes. “That same kind of philosophy carried over to Tolson Park. Kids were taught education is just as important, if not more important, than recreation and athletic events. …

“He comes across (a tough guy) and he wants the kids to respect him. (He would) teach kids self-discipline and respecting elders, but at the same time, he has a huge soft spot for the community or else he would have gotten out of this business 40 years ago.”

He wasn’t done with politics, either. Barnes played a key voter turnout role for Mayor James Perron’s 1995 re-election campaign, and he won a seat for himself on the Elkhart City Council in 1999. It was a job he kept until his death Sept. 22, 2003.

Arvis Dawson collected Barnes’ nameplate at city hall that evening and delivered it to the family.

Dawson called Ben Barnes his hero.

Barnes passed away at Elkhart General Hospital four days after suffering a stroke. About two-thirds of the following day’s front page carried tributes to the Elkhart legend. Reporters Overton and Rick Meyer knew him well and put simple, poignant words in the lead of their story:

“Ben Barnes spent a lifetime touching other lives. He was a father, youth director, boxing coach, community volunteer, senior advocate, politician and – maybe most of all – a friend.”

In his Sept. 27 eulogy, the Rev. Theodis Hadley said, “(Ben) didn’t spend his time worrying about what he did not have. He spent his time using what he had.”

‘My friend who lived it and rose above it’

Ben Barnes’ impact in his hometown spanned decades. His work lives on each time a young person gets off the street and into the boxing ring or community center.

His words, his attitude, his outlook live on in his book, which almost didn’t even get written. Co-author Kathlyn Gay met Barnes at a party in early 1971, and had to convince him over several months to give it a try.

Erickson wrote, “Every Tuesday after work, she’d record interviews. ‘After work’ for Barnes often meant a late start because he almost always has held two jobs – sometimes three.”

They discovered a great working partnership. More writing followed, including a book about amateur boxing when the tables turned and Barnes had to convince Gay about its value. The families also joined together to rehab southside homes.

When Barnes passed away, letters celebrating his life were printed on the opinion page for days. Gay contributed one of her own.

“Ben Barnes. He was my friend, my soul mate for so many years,” she wrote in September 2003 from her home in New Port Richey, Fla. “… I grieve, my family grieves, but I know his family and everyone who knew him well feels the pain even more acutely. I ache, but I know everyone who felt his influence feels the same way. I cry, but I know that he taught me that it’s OK to cry, to emote, to be passionate about issues that matter. …

“I learned to be part of a community when during the 1970s the Barneses and the Gays became involved in refurbishing houses and renting them to people in the neighborhood. What a great time it was to be knocking out walls, painting, cleaning, or disinfecting old houses and have neighbors come by to find out what was going on or to feel the sense of accomplishment after hours of hard physical labor. I relish that opportunity I had to work and learn.

“Learning is part of listening, which is what I did when writing the three books Ben and I co-authored. … I relish that listening, because Ben was a talker and he had a lot to say and I had a lot to absorb. In fact, white folks of my generation still have a lot to learn from their neighbors whose skin color (or religion) doesn’t match theirs.

“This has been obvious as we’ve moved from the middle part of the country to the third-world state of Florida. Here one can still see the hard-core remnants of segregation, bigotry, and intolerance. It gnaws at my soul, but I think of my friend who lived it and rose above it, and taught his children to do the same.

“Do you know what else I relish? Having a long-time friend I could argue with, call names, swear at, refuse to speak to at times, drink booze with, drink coffee with, invite to parties, go on walks with, talk politics with, trust him with all my kids, proudly introduce him to all my extended family, and point to him as a role model in many, many instances. That’s what real friendship is all about and I know my life has been enhanced by that friendship.

“In short, Ben goes on living – in my life and in countless others.”