Judge Redding wanted reform but failed to beat Cosentino

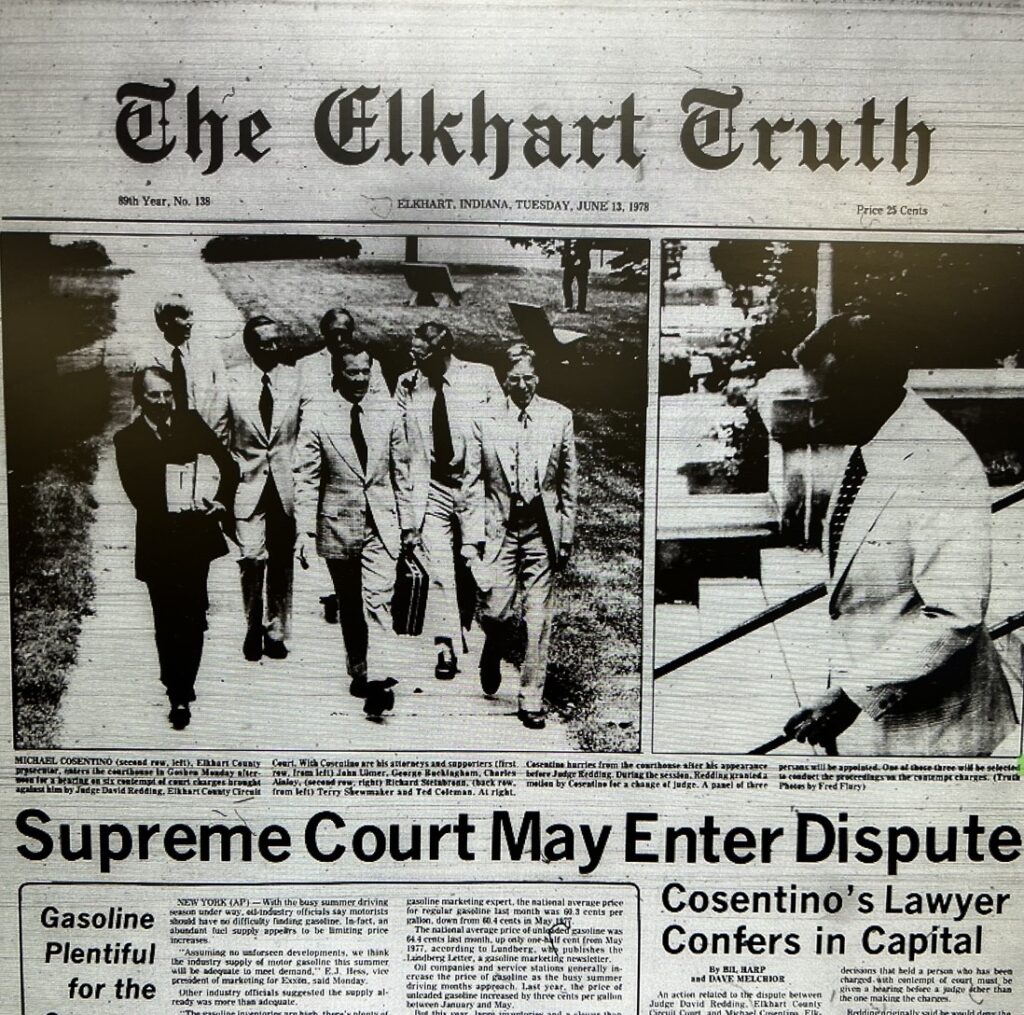

A brigade of men in light-colored suits moved confidently on the sidewalk leading to the Elkhart County Courthouse. In the middle of this who’s who of local lawyers was the accused: legendary prosecutor Michael Cosentino.

Circuit Court Judge David Redding had had enough. He halted a grand jury’s work to level six counts of contempt against Cosentino.

But the judge had his own troubles. Attorneys had openly opposed his election. Defendants made moves to keep their cases from his court. And less than three years after his admission to the bar, the state was investigating a complaint about Redding’s professional competency.

The courtroom was bursting with gawkers. On this otherwise seasonable Monday afternoon in June 1978, the power struggle between judge and prosecutor was boiling.

Elected for change

David Redding accomplished the impossible in May 1976.

In his mid-30s, Redding won the Republican nomination for Elkhart Circuit Court judge. His opponent, incumbent Aldo Simpson, was first elected to the bench in 1932 – at 44 years, it was longevity in a judicial position that still stands as a state record.

After Redding denied Simpson re-election, he defeated Democrat Ray Eberhart in the general election. Upon taking the bench in January 1977, Truth reporter Dave Overton wrote, “Out of respect for the man who held the position for all of those years … (Redding) is trying to ease into the judgeship with a minimum of change.”

But Redding was elected to shake up the status quo. His campaign ads demanded “Decisions Not Delays” in reforming local courts.

He advocated for Elkhart County to embrace the state Supreme Court’s new rules for modernization.

He wanted people to have the ability to represent themselves.

He saw an opportunity to ease the stress on heirs by settling estates more quickly.

And he believed, as he stated in the Oct. 30 Truth election preview article, the court “backlog could be substantially reduced and the cost to parties of litigation minimized.”

“I feel that this complete overhaul represents the most significant change and benefit for the people to occur in 100 years,” Redding’s 1976 campaign ads stated. “… We are beginning reform that is 50 years overdue.”

But 56 attorneys balked at Redding’s attempt to win the bench, and uncharacteristically said so publicly before his election. Many of those same lawyers said they had no interest in filing civil cases in Redding’s circuit court.

This was only the beginning of the contentious relationship.

The opening statements

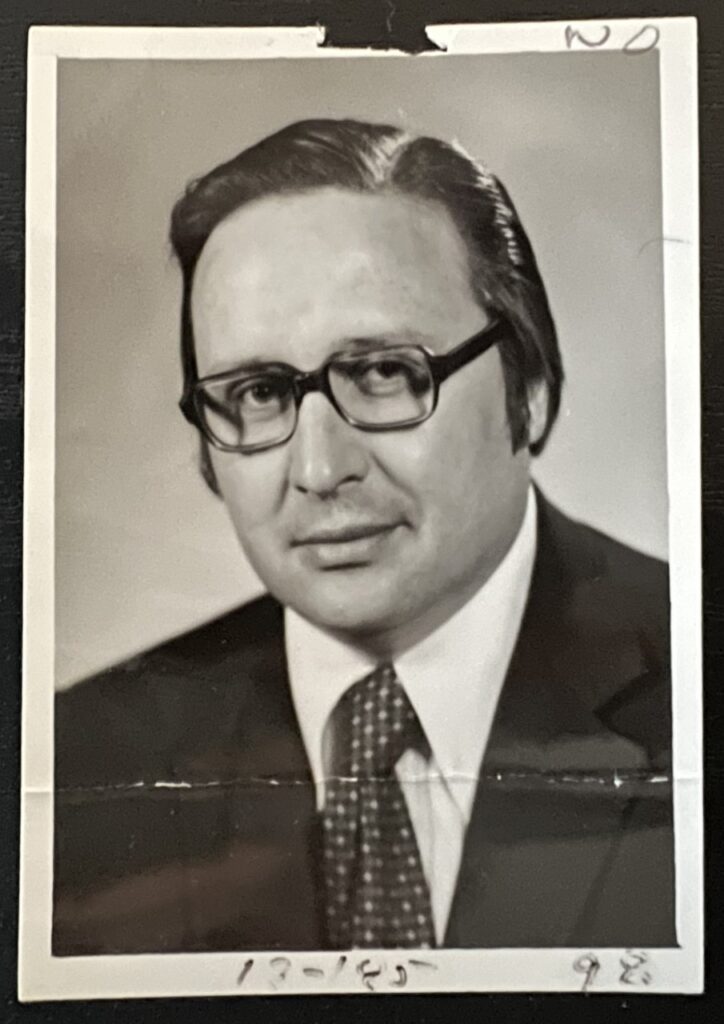

Michael Cosentino was no-nonsense. He reacted strongly and swiftly.

After Redding levied a $25 fine at deputy prosecutor R. Gordon Lord for failing to prepare for a hearing, Cosentino immediately called the judge. And the prosecutor immediately ended the call when told he was being recorded by the court reporter.

This incident was just six weeks into Redding’s tenure. Cosentino responded by pulling criminal matters from the court, and for at least four months starting May 2, Redding received no new filings.

The judge took the simmering dispute public. He made pointed comments to the county council about the newly assigned deputy prosecutor, Terry Shewmaker, receiving his weekly pay though no cases were being filed in Circuit.

In a Sept. 15, 1977, Truth article about the lack of cases, Redding said, “Since taking office, I have attempted in every way possible to conduct this office with dignity. The situation has become so grave as to threaten the safety, security and protection of the citizens. I think it is now time for me to speak out. … Not once have I been reversed in any of my decisions. There have not even been any complaints about my decisions. I don’t understand what the problem is.”

The Elkhart County Bar Association stepped in to mediate. Attorney George Buckingham said the meeting was “open and frank” and “best left private.”

The truce was short lived.

Unhappy attorneys

By the start of winter, Redding said lawyers were making it impossible for him to do his job. Case filings had resumed, but defendants were now seeking a mandatory change of venue.

“If it comes to the point where I cannot do the job 22,000 people hired me to do, I’ll resign,” Redding told Truth reporter Bil Harp for the Dec. 5, 1977, edition. The law allows the “defendant in a criminal case to fire the judge. This causes a great deal of difficulty. There is no reason for a defendant to keep the judge and every reason for him to get another one.”

The judge soldiered on, though.

In May 1978, he again angered attorneys by adopting a no-fault divorce policy, allowing couples to split by representing themselves if property and child custody issues were not significant. Average costs, Redding said, would drop from $485 for the cases down to $28.

“(Only) about one of every 200 or 300” divorces are that simple, Goshen attorney Dick Mehl told The Elkhart Truth. “I don’t know of many people who do not have any property or children. It’s like a loose tooth; if there are no complications, there is nothing keeping a man from tying a string around it and pulling it himself. But if you have complications, you go to a dentist.”

And then, Mehl delivered the punch: “If Redding’s court isn’t any more crowded than that, I think it is wonderful he’s helping these people. I think it’s wonderful he’s doing something with his time.”

The pressure builds

Redding also was critical of how Sheriff Dick Bowman ran the county lockup. The judge had ordered more visiting hours and greater telephone access for inmates, and he began reviewing sentences of greater than 60 days.

An inmate’s death in November 1977, though, provided Redding with an opportunity to take even greater authority on jail conditions.

It did not go well.

The first grand jury was dismissed when Redding said it did not follow his instructions. Jurors had toured the jail and reported it was in “neat and orderly condition. … Jail rules were studied and found to be complete and up to date,” with no encroachment of civil rights.

Before the second panel could even begin to meet, the husband of an original grand juror filed a complaint with the Indiana Judicial Qualifications Commission. At issue: “The qualifications and rationality of determinations of one David Redding.”

Cosentino told Truth reporters he had no issue with the first grand jury’s findings.

The pressure on Judge Redding was building.

The prosecutor was ready for the fight.

No more ‘schoolboy lectures’

On June 8, 1978, something unusual happened on the third floor at the old Courthouse. The grand jury called for its next witness: Judge David Redding.

“An obviously flustered Redding stormed from the bench and started toward the jury room,” Truth reporter Bil Harp wrote, “demanding as he went to know why a crowd of reporters had gathered outside the courtroom. Redding also ordered all cameras removed from the premises.”

Harp himself, along with fellow reporter Dave Overton, already had taken their turns in front of the grand jury. The reasons for the questioning were never stated in print.

Redding’s statements in his 10 minutes inside the jury room also went unreported in the newspaper. His next actions, though, were fully on the record.

The judge ordered Cosentino immediately removed from his role as grand jury advisor. The prosecutor had said earlier in the week Redding was acting outside his authority in instructing the panel.

When the grand jury requested Cosentino return after lunch, Redding approved. The judge then had a change of heart. As soon as Cosentino rejoined the panel, Redding stormed into the grand jury room with his court reporter, demanding a record be kept of the conversations with the prosecutor.

After a closed-door hearing between judge, lawyers and jurors back in the courtroom, the panel was adjourned for a week. Cosentino said, “No comment. I have been discharged.”

John Ulmer, representing the prosecutor, asked the judge to reconsider. Instead, Redding slapped six counts of contempt on Cosentino, each with a penalty of up to three months in jail and a $500 fine.

According to the contempt filing, Judge Redding said Cosentino “in a loud and angry and contemptuous manner” stood in open court and quoted the prosecutor as saying, “You are wrong. I am going to stay with this grand jury, your honor. You cannot do that. I have done my duty and will continue to do so.”

The defiance, according to the filing, “tended to place the judge in a position of contempt before said grand jury.”

Cosentino also was charged with telling the judge to “get out” of the grand jury room. Another count said Cosentino told Redding he “would not listen to any schoolboy lectures” and turned his back on the judge to leave the room.

‘The spectacle’

“It’s regrettable to see the Circuit Court a center of controversy,” The Truth’s Larry Murphy wrote in his June 13, 1978, editorial. “In the current atmosphere surrounding the court, there is bound to be a quantity of speculative talk. The spectacle of hauling the county prosecutor into court on contempt charges doesn’t happen every day.

“Yet this is no occasion for snickers. The breakdown of cooperation between judge and prosecutor in the judicial process is a grave matter affecting the administration of justice. …”

To answer to the contempt charges, Cosentino walked to court with his contingent of great legal minds. Future State Rep. John Ulmer. Future Circuit Court Judge Terry Shewmaker. Highly respected attorneys George Buckingham and Charles Ainlay.

Cosentino won a small victory that day, smiling and shaking hands with supporters after Redding granted a change of judge for the contempt hearings.

“We may hope that under a new judge the issues here will get a sober hearing and a reasoned determination,” Murphy wrote in the editorial.

Within a few days, the contempt charges were dropped altogether. Cosentino returned to the grand jury room, and Redding instructed the jury as he wished. Following the interview of the 20th and final witness, the grand jury found “no knowing or intentional criminal recklessness” that led to the inmate’s death.

The power struggle between judge and prosecutor was, for all intents and purposes, over. The same could not be said for Redding v. Other Attorneys.

Resigned to the ending

Redding avoided discipline and suspension by the state on Oct. 19, 1978, when the Judicial Qualifications Commission released its decision on the competency complaint.

“I’ll let the findings speak for themselves,” Redding told Harp. “I recognize a judge cannot make correct decisions 100 percent of the time. However, the past 30 days have been rewarding since the Indiana Court of Appeals has upheld this court’s ruling on three separate occasions, and the commission has determined the court acted within its judicial discretion.”

The judge continued on his campaign to change jail operations and conditions, and took on an expanded role in juvenile court proceedings.

But he also kept on antagonizing local attorneys – behavior that led to the end of his time on the bench.

On Oct. 23, 1979, The Truth’s David Schreiber wrote Redding had resigned “after he was made aware of allegations of judicial misconduct and abuse of discretion made against him by Elkhart County attorneys and other citizens.”

Petitions had been circulating requesting the state review the matter, and as many as 20 attorneys submitted affidavits alleging specific acts of abuse and misconduct. Goshen lawyer Tom Leatherman said the Goshen Bar Association had given Redding the choice of resignation or investigation.

Leatherman notarized the resignation letter, Schreiber wrote, and it was flown to Indianapolis for Gov. Otis Bowen to receive.

A day later, Judge Redding blamed the pressure to resign on the heavy juvenile caseload he had been taking. He blamed his stress on having “spoken a little harshly with certain individuals outside the courtroom.”

Redding later told The Truth he was going to ask the governor to tear up his resignation. But Bowen appointed Gene Duffin, who took the bench on Jan. 1, 1980.

After serving just half of his six-year elected term, Redding went back to private practice.

“My mistake, if any,” Redding said after Duffin’s swearing in, “… was working too hard for the people of Elkhart County.”