The Klan wanted influence. One Elkhart leader took a stand.

A man about to become Elkhart mayor sent a letter to a power-hungry and murderous Ku Klux Klan boss.

The year was 1925. The letter needed no follow up. David M. Hoover’s courageous words were clear.

In the 1920s, the Klan’s outsized influence dominated Indiana politics. The secretive group twisted patriotic themes and motivated listeners to “protect the nation” from the immediate threats posed by socialists, Catholics and Jews, as well as people of color.

Membership in Indiana numbered in the hundreds of thousands – perhaps as many as a third of all Hoosier men belonged – and D.C. Stephenson was the lead recruiter and lobbyist. Elected officials all the way to the governor’s mansion were guided by his hand.

Stephenson wrote often to Hoover and other Republican county chairmen throughout the 1924 election cycle, looking to secure their cooperation. On March 7, 1925, he sent a letter applauding Republicans for keeping leadership “in the cleanest hands” and “guided from the most lofty motives.” He offered the “friendly suggestion” that party leaders select the right men in the upcoming city elections.

D.M. Hoover picked this moment to respond.

Whatever the future held, Elkhart’s next mayor would not be Stephenson’s next puppet.

The growing ‘menace’

Throughout its history since the Civil War, the Ku Klux Klan has engaged in unabashed intimidation and violence. But in the years after World War I, the hate group gained traction in northern states with different tactics and ambitions. Doctors and professors, middle-class laborers and ministers listened to the arguments rooted in Protestant ideals, particularly temperance in the age of Prohibition.

“Easterners have been surprised at the ready conquest by the Klan of a state which seemed of all our forty-eight the least imperiled by any kind of menace,” the New York Times wrote about Indiana in 1923.

D.C. Stephenson was well prepared to be the lead convincer. His past remains cloudy, but it is known he learned his tactics observing how socialists fired up their followers. He moved to make the Klan a powerful political force with an undeniable voting bloc.

He signed on and made money with each KKK membership secured – averaging 1,000 a week for a six-month period in 1923. Earning the nickname “Old Man of the Klan,” Stephenson ascended to grand dragon at age 32. He wrangled support for Ed Jackson to win the 1924 governor’s race, all in hopes of securing an appointment to the U.S. Senate for himself.

Stephenson lusted for money-making schemes. He sought control over all Republicans in elected office. He had personal ambitions for the White House.

“To think that Stephenson had plotted to become president of the United States may sound farfetched today,” author M. William Lutholtz wrote in his biography of Stephenson. “But in 1923, it was also farfetched to believe that either Hitler or Mussolini – both contemporaries of Stephenson – might one day seriously threaten most of Western civilization with their own dictatorships.”

Generally, many Democrats were vocal Klan opponents. Carelton McCulloch, the party’s nominee for Indiana governor in 1924, said, “The recent primary election has made a clear cut issue of a question which does not belong in politics at all. The republican party has been captured by the Ku Klux Klan and has as a political party ceased to exist in Indiana. The democrats must accept the challenge and fight for the principles of religious liberty and constitutional guarantees of the state and of the nation.”

Republicans tended to walk a fine line, even at the national level. U.S. Sen. James Watson, R-Ind., told state convention goers, according to a May 1924 Elkhart Truth report, “he was not a member of the Ku Klux Klan, but had no objection to any man belonging to if he desires.” President Calvin Coolidge dodged taking a position on the Klan during election season, though his vice presidential running mate did not duck.

“Whatever the high purpose they claim – whatever they may be called – take the law into their own hands, force rises to meet force; lawlessness rises to meet lawlessness and civilization commences to disintegrate into the savagery from which through the ages it has evolved,” said Republican Charles Dawes in August 1924. “Appeals to racial, religious or class prejudice by minority organizations are opposed to the welfare of all peaceful and civilized communities.”

Interest in Elkhart

With Stephenson directing the show of political strength, the Klan anticipated 100,000 followers – 1,000 of them from Elkhart – to attend a Fort Wayne rally in November 1923. By May 1924, on the week when Republicans gathered for their state convention, 200,000 Klansmen in full regalia convened in Indianapolis.

The local contingent was still growing.

The Elkhart County women’s order of the Klan had an “open air meeting in a field bordering the Lincoln Highway just north of the church at Dunlap” to initiate 115 new members, according to June 19, 1924, Elkhart Truth. “Robed klansmen served as guards to keep the crowd of 1,000 back,” the report noted.

Then, on Oct. 13, 1924, 150 boys participated in the Junior Klan Field Day at McNaughton Park in Elkhart. The Truth reported attendance was kept down due to the football game at Rice Field.

“The establishment grew so strong and bold it was planned to seize power at all government levels, including national,” wrote Hoosier historian J.M. Guthrie in a 1960s era Elkhart Truth opinion piece. “Knights bragged that theirs was the most effective political organization the United States ever had.”

But the Klan itself was fracturing.

The Indiana faction disagreed with the Southern contingent, and spin-off groups like the “Knights of the Flaming Sword” and “Independent Klan of America” appeared. After tangling with Walter Bossert for state leadership, Stephenson – at least in public reports – “retired” from his grand dragon position.

He remained a trusted advisor to incoming Gov. Ed Jackson. After managing the campaign, he assumed the point position with the legislature. As a lobbyist for everything from road improvements to margarine production, he only had intentions to be paid for securing lucrative government contracts.

He also wanted to control the entire Republican Party structure.

Letter perfect

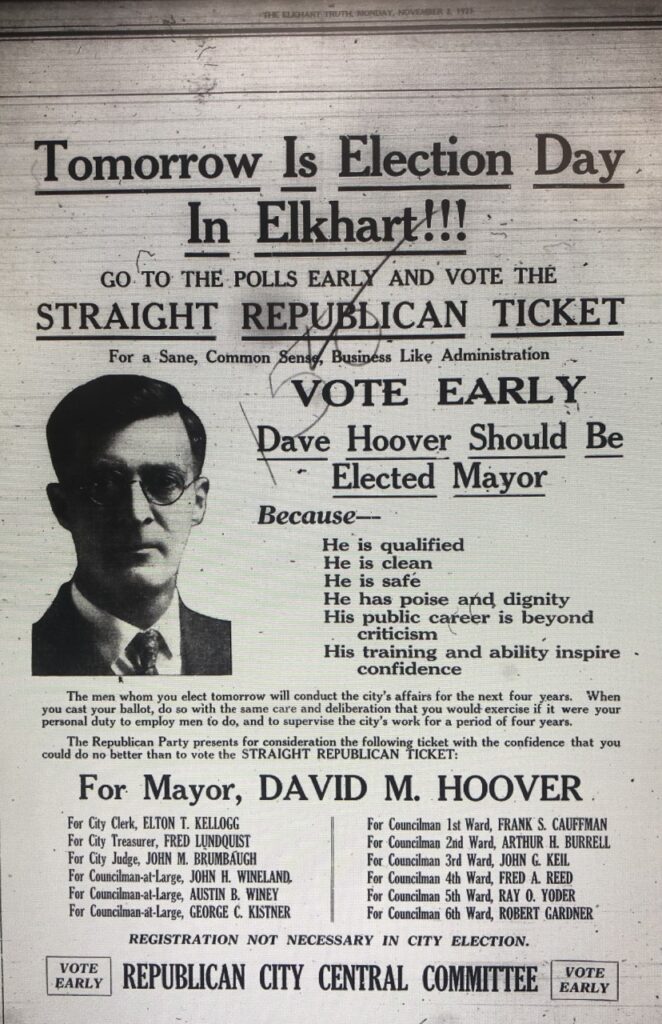

D.M. Hoover graduated from the University of Michigan law school in 1909 and started on his way to a prominent career. He was elected city court judge before he became leader of the local GOP in 1922. As the head of the party, Republicans won the vote majority in all elections – county, state and national.

When he announced his campaign for mayor on Feb. 17, 1925, Hoover said, “If I am nominated and elected I will see to it that Elkhart is given a clean and business-like administration.”

Stephenson wanted to be part of that business.

“Mr. David M. Hoover,” Stephenson’s letter of March 7, 1925, began. “The Legislature is just about over. It has made a brilliant record … no Legislature assembled in Indiana has come nearer satisfying all the people of the State.”

The Klan boss poured praise onto Republicans, and noted local party organizers are operating “with less strife and discord than at any time within the past fifteen years. Let’s keep the standard high. …

“So far as I am concerned, it makes no difference who you support, and certainly I do not want to be in the attitude of attempting to dictate, but merely offer a friendly suggestion that you back a vigorous man for Mayor. … I only want to help in a constructive way, the men who rallied to the standard of the Republican party at a time when I felt my own reputation and business future was psychologically interwoven with the success or failure of the Republican ticket.”

Hoover, one of four candidates seeking the party’s nomination for Elkhart mayor, did not delay in responding. His letter was dated March 10.

“I wish to take this occasion to ask you just who you are, anyway?” Hoover wrote. “… How comes it, that you assume such a god-fatherly attitude toward us all? … Just why should you think that Republican County Chairman might heed or even care to receive your abundant, gratuitous advice?

“Were I to write just such letters as you have been writing to me, to the county chairman of Marion county, he would immediately engross my name into his register of egotistical fools.”

Hoover was far from finished.

“I fail to understand why you should assume such a paternal attitude toward me. … You have given me much free and unsolicited advice. Now, permit me to advise you just this once. My advice is that you take a look at yourself as others see you, and that you withdraw your ‘steadying’ hand from the state of Indiana and see whether it can wobble along without your generous assistance. We always did get along, somehow, without you. And I think we could manage to do it again.”

>> Read more: Stephenson’s letter and Hoover’s reply, as printed in the Anderson Herald on April 22, 1925 <<

Stephenson could not have been pleased. By the time the exchange became public, though, both men were making headlines for much different reasons.

Klan boss ‘all done now’

Stephenson met Madge Oberholtzer at Gov. Jackson’s inaugural in January 1925. Their relationship grew as she began working as a Statehouse aide, and took a stunningly violent turn two months later.

Oberholtzer was kidnapped from her parents’ home. Stephenson was drunk and assaulted the young woman on a train bound for Hammond, Ind. She was brutally beaten and bitten, and left cold and defeated as a prisoner for a few hours in Stephenson’s home. One of grand dragon’s men gave her money to buy a hat for her return ride to Indianapolis; instead, she purchased the corrosive bichloride of mercury and swallowed it.

A Marion County grand jury issued five indictments against Stephenson on April 3, 1925. Oberholtzer’s fading condition was watched closely by newspaper reporters. Her death by suicide was the banner headline on April 14. The grand jury upgraded a charge to first-degree murder, and Stephenson was denied bond.

His conviction was months away. Newspaper did not waste time in declaring his influence dead, scrambling to keep the Klan boss’ name in headlines and opinion pieces.

“The career of Stephenson, so long as it lasted, was spectacular, and in a large way he got away with what he was trying to do,” the Anderson Herald wrote in an editorial reprinted April 25, 1925, in The Truth. “In getting away with it he did a great deal toward discrediting the republican party.

“Stephenson is no fool and he evidently remembered a war condition that ‘to be a leader the most necessary was to step out in front and give orders.’

“Stephenson with his hold on the klan arrogated to himself the leadership of the republican party and in primaries and convention of a year ago he had his way all over the state. Then he assumed management of the campaign. He cowed those officially in charge, and under the saving grace of ‘Coolidge for President’ he ‘won’ a victory.

“Later he took possession of the legislature, claiming that nearly two-thirds of the membership would do his bidding no matter what it was, and he became a lobbyist, ‘saving the state’ usually for reasons of his own, and pulling out jobs for his henchmen.

“… There is not instance in the political history of the state that compares with this stunt staged by this comparatively young lodge organizer. Reflecting on skyrockets he was one. He had some ability and a monumental nerve. This was all spent in an idle just for power, and the way he moved about would have made a P.T. Barnum envious.

“But Stephenson is all done now. He is indicted and in jail for the commission of the most heinous crimes on the calendar and he is still strutting and bragging, though just at present behind iron bars.

“One point is that Stephenson ‘now’ is identical with the Stephenson ‘then.’ He is and was a false alarm. … Stephenson is gone but how can we forget him!”

Headline grabbers

The Anderson Herald became the first to publish the Stephenson-Hoover exchange on April 22, 1925. Lending perspective to the letters, which were written weeks before Stephenson’s indictment and arrest, the Herald wrote, “Evidently, Mr. Hoover was not disposed to accept a straw dummy for a real man and accordingly ‘called’ (Stephenson) in no uncertain way. This is the first publication of these two letters, the one typing the invisibility of the Stephenson ‘management’ and the other being a retort that speaks loudly of the sagacity as well as the punch of Mr. Hoover.”

Newspaper editors found plenty of reasons to track the daily movements of the secret society during the mid-1920s. The near-daily reports were significant to ensuring the Klan’s power faded.

“The Klan wielded too much power and became corrupt, particularly in high places. Internal dissension broke its ranks and cliques fought for control. … (V)igilant Hoosier newspapermen began to go to work on the Klan and literally took it apart by exposing its rottenness,” Hoosier historian J.M. Guthrie wrote. “Good-citizen members quickly and quietly dropped out when they discovered the real Klan which they had joined. By 1926 it was through.”

The Elkhart Truth published the Stephenson-Hoover letters two days after the Anderson paper ran them. While the Klan had made bold front-page news in Elkhart for more than a year, the headline “Hoover Is Tart To Stephenson” appeared on page 14 of the day’s paper. Editor Tom Keene included the Anderson Herald editorial on the Truth’s opinion page the next day.

In coverage of the race for mayor, The Elkhart Truth did not mention Hoover’s rejection of the Klan. The candidate also maintained his focus.

“My record as such judge is well known. I then stood, as I now stand, for law and to arrive at the absolute justice, insofar as that is humanly possible,” Hoover wrote in response to The Truth asking why candidates believe they should be elected, published April 23, 1925. “Elkhart is no longer a mere country town. It is an industrial city. Its stead and unimpeded growth and prosperity during all these post-war years have attracted nation-wide attention to our city.

“We are a progressive and a forward-looking community. I have unbounded faith in Elkhart’s future. I feel that almost any prediction that I could make regarding Elkhart’s immediate future might be surpassed by its attainments in the next four years.

“It is my ambition for Elkhart that it meet and anticipate all the needs of an ever growing city; that its business be conducted in the same sane and careful manner in which a prudent man would conduct his own affairs; that it be orderly and attractive; and that its inhabitants be prosperous content, law-abiding and happy. To the accomplishments of these ends I have always directed my efforts as a citizen. To their further advancement I am willing to dedicate any talent that I may have, as mayor.”

Hoover defeated William Sigerfoos by 75 votes out of more than 4,100 cast in the May 1925 primary. He defeated incumbent Frank Leader in the fall to become Elkhart’s 21st mayor.

Different legacies

Hoover did not seek election to a second term in 1929. He oversaw the implementation of a city building code, the rehabilitation of the fire alarm system, and the installation of lights at McNaughton and Island parks.

But his administration had its critics. A much-needed upgrade of the downtown sewer system resulted in lengthy traffic disruptions and was disparaged as “Hoover’s Ditch.”

He also sought to establish an airport on the north side. “I believe that a municipal airport in Elkhart will prove of as much benefit to the city in time as does the main line of the New York Central now.,” he said. “… Aviation is with us to stay (and) it will grow in importance rapidly. … Elkhart is very fortunately located, has great possibilities of becoming an important unit of the vast system of ports that will soon dot our entire country.” Voters rejected the plan by a wide margin in the November 1929 election.

Hoover left office in the opening days of the Great Depression. The city had a $67,000 budget surplus and no debt. He returned to his law practice for a short time until his 1932-36 assignment as local postmaster. He fulfilled his party duties as a presidential elector several times, including for Wendell Wilkie in 1940.

Hoover died Sept. 28, 1956, and is buried at Rice Cemetery.

Stephenson’s conviction in Oberholtzer’s death sent him to prison until the 1950s. Denied clemency by Gov. Jackson, the former Klan boss engaged in one last power play from his cell. He revealed to newspaper reporters a wicked web of bribery schemes and other illegal activity. Even Jackson was ensnared, and while he avoided conviction on a technicality, he was personally disgraced and left office after one term.

In 1961, Stephenson was charged with assaulting a 16-year-old girl, though prosecutors dropped the charge after a fine was paid. The one-time grand dragon then sought anonymity and a fourth wife, finding both in Jonesboro, Tenn.

Until a 1978 investigation by the Louisville Courier-Journal, the general public didn’t know the once-powerful KKK grand dragon had died of a heart attack 12 years before.

(Special thanks to the Anderson Public Library for research assistance on this local history post.)